Search

Regions

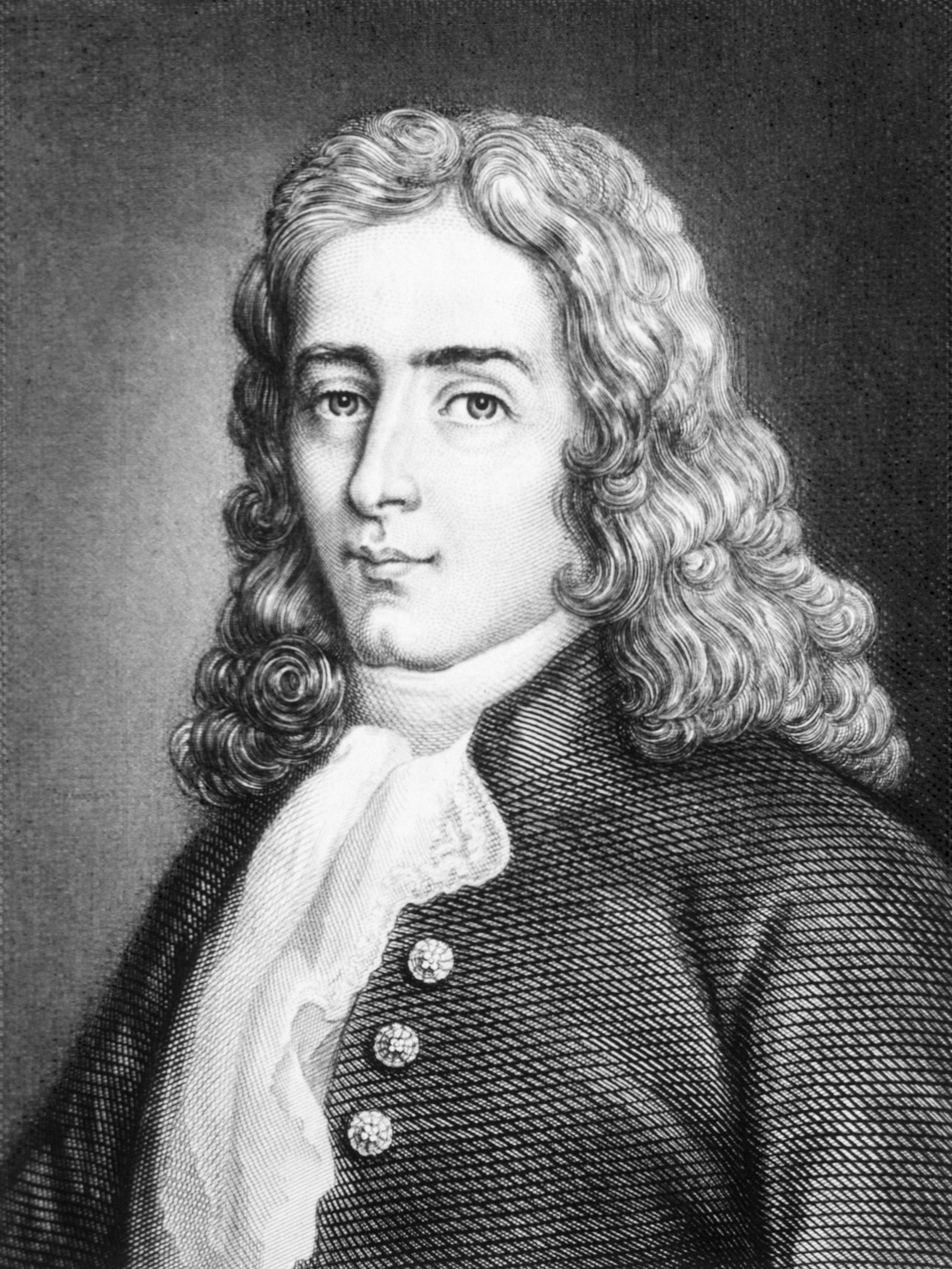

René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

(1683-1757)

New France was a French colony from its founding until the British conquest of Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760. Given France’s important place in European natural science, the lack of early ornithological material from New France is puzzling. The first important bird records from New France included in Mathurin-Jacques Brisson’s (1723-1806) Ornithologie, were not published until 1760, just at the moment when France was forced to give up its first North American colony.

Brisson’s Ornithologie was a pioneering work in the development of the science of ornithology. It also contained many scientific descriptions of Canadian birds. While Brisson had access to the published ornithological writings of early visitors to New France such as Sagard, Denys, LaHontan, Kalm and Charlevoix, he made little reference to their records in Ornithologie. Without a specimen, a brief description of a bird giving only its name or a brief account was not considered an acceptable record.

For written material on North American birds, Brisson relied on the works of the British naturalists, in particular Mark Catesby’s Natural History of the Carolinas, Florida and the Bahamas, 1729-47, and George Edwards’ A Natural History of Uncommon Birds (1743-1751) and Gleanings in Natural History (1758-1764). Both Catesby and Edwards based their descriptions on living birds as well as skins or mounted specimens in public and private collections. Edwards included records of Canadian birds collected by traders in Newfoundland and employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Neither Catesby or Edwards described a specimen collected in New France.

Brisson also relied on specimens from around the world in the collections of France’s most important 18th-century collector, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683-1757). Réaumur’s collection contained specimens from New France.

René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur was a prominent member of the Académie des Sciences, and a wealthy nobleman who held no official positions in science or government. Réaumur originally studied law and then mathematics. He was elected to the Académie in 1708 at the age of 25. Initially Réaumur studied the properties of iron and steel and invented a new thermometer before turning his attention to insects. He is best known for his Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des insectes in 6 volumes, published between 1734 and 1742.

Like his contemporary Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) in England, through his wealth and contacts Réaumur accumulated the finest collection of natural history specimens of his time. He started his bird collection in 1743 (Trembley: 1936). In the mid-18th century the science of preserving bird skins was, however, still in its infancy. Farber noted in The Emergence of Ornithology as a Scientific Discipline 1760-1850 Réaumur’s frustrations with the difficulties of preservation:

No considerable collections have hitherto been made [because of] the Mortification to see them every Day destroyed by ravenous Insects in spite of all the care that had been taken to preserve them against their Teeth.

To assist in the preparation of specimens Réaumur studied taxidermy, examining mounting techniques and perfecting a method of preparing skins by drying in an oven, which helped to retain a lifelike appearance. He published his findings and encouraged his many natural history correspondents to apply his techniques and send him prepared birds. His treatise was also translated into English as “Divers Means for Preserving from Corruption Dead Birds, Intended to Be Sent to Remote Countries, So That They May Arrive There in a Good Condition. Some of the Same Means May be Employed for Preserving Quadrupeds, Reptiles, Fishes, and Insects”, and published by the Royal Society in 1748. Réaumur also instructed his collectors to send numerous specimens and their nests, and to write notes on habitat and behaviour.

Réaumur was the most important natural scientist of his generation. Using his curiosity, careful observation and experiment he carried out numerous studies that advanced other aspects of ornithology. These included experiments on the digestive juices of birds, the artificial incubation of domestic fowl and speculations on the forms of birds’ nests.

To deal with his growing collection, in 1749 Réaumur hired Mathurin-Jacques Brisson. Thus, in preparing his Ornithologie, Brisson benefited from the vast amount of information collected by Réaumur, and was able to identify where species came from, who collected them and to provide ecological and life history details.

For birds collected from Canada (New France) Brisson relied heavily for his descriptions on specimens sent to Réaumur by Jean-Francois Gaultier, the Médécin du Roi for New France, and Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, who for a short time (1748-49) was Governor of New France. Ornithologie also featured some of the first engravings of Canadian birds, prepared by the French artist, François Nicolas Martinet.

Despite the importance of the colony of New France, and its proximity to France, the vast majority of specimens in Réaumur’s collection described by Brisson, were from Europe, Central and South America, Africa and Asia. The waterfowl and raptors of northern Europe, which are larger birds and easier to collect, were similar or identical to Canadian species, and hence the acquisition of Canadian birds was deemed unnecessary. Species from less known lands, especially from the tropics, were often more colourful and many were morphologically distinct, and thus more desirable to collect.

Nevertheless, Brisson attributed about twenty-seven records in the Réaumur collection to New France. The majority - twenty-one - were collected by Gaultier, and the rest by de la Galissonière. Additional species attributed to New France, but excluded here, were collected from Louisiana by de la Galissonière. Erwin Stresemann in his Ornithology from Aristotle to the Present noted that Brisson also used the “extensive collections” of Abbe Jean-Thomas Aubry (1714-1785) and the physician Mauduyt de la Varenne (1732-1792). Brisson found five additional species from New France in the cabinet of Aubry. At this time it is not known where Aubry obtained his Canadian specimens. Brisson does not mention any specimens from Canada from de la Varenne’s collection, which was largely assembled at a later date.

Quebec ornithological historian, Michel Gosselin, has written a paper “Les Oiseaux de Jean-François Gaultier” published in Québec Oiseaux (Winter 2019). Accounting for duplicate records, he attributes twenty species to Gaultier and seven species to de la Galissonière.

Brisson’s records from New France are unique. They represent species from a geographical area far removed from the Hudson and James Bay lowlands, the other major collecting site in early Canadian ornithology. As a result, they include many first records for Canada.

With the arrival of Georges Leclerc, Baron Buffon (1707-1788) as superintendent of the Jardin du Roi in the 1730s, and Réaumur’s death in 1757, Réaumur’s huge collections became the property of the Jardin du Roi. In the last half of the 18th century Buffon continued to maintain the Jardin’s natural history collections, the finest in Europe. Buffon wrote extensively on natural history, including his ten-volume Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux published between 1770 and 1786. Buffon’s reputation as an ornithologist, based on his strong interest in field studies and ecology, greatly benefitted from the pioneering work of Réaumur and Brisson. Perhaps cut off from ties to Canada, Buffon’s Histoire Naturelle contains no new records from Canada.

Réaumur, through his encouragement of collectors in the French colonies, including New France, and similarly Sir Hans Sloane, who encouraged the collecting of specimens by the Hudson’s Bay Company employees, laid the foundation on which our knowledge of 18th-century Canadian ornithology is based.

Today Réaumur is primarily known as one of the first ethologists (behaviourists), with a particular passion for insects. As a pioneer in ethology, his writings influenced not only Buffon but also Gilbert White (1720-1793), who published his famous book, Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne in 1791. No doubt Réaumur’s interest in insects and behaviour also had a significant influence on the great French naturalist, Jean-Henri Fabre (1823-1915), who is considered by many the father of modern entomology.

Darwin’s champion, Thomas Henry Huxley, was a great admirer of Réaumur. Introducing Darwin on his receipt of an honorary LLB from Cambridge he noted “I know of no one who is to be placed in the same rank with [Darwin] except Réaumur.” (L. Huxley, Life and Letters of Tomas Henry Huxley).

Bibliography

- Brisson, Mathurin-Jacques. 1760. Ornithologie. Paris: L’Imprimerie d'Antoine Boudet, Imprimeur du Roi.

- Buffon, Baron. 1771-1786. Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux 10 Vols. Paris: l'Imprimerie royale

- Farber, Paul. 1997. The Emergence of Ornithology as a Scientific Discipline 1760-1850 Baltimore MD: John Hopkins University Press

- Huxley, Leonard. 1900. Life and Letters of Tomas Henry Huxley 2 Vols. London: Macmillan.

- Réaumur, René Antoine Ferchault de. 1734-1742. Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des insects 6 vols Paris: Académie Royale des Sciences.

- Stresemann, Erwin. 1975. Ornithology from Aristotle to the Present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Trembley. Maurice. Edit. 1936. Correspondence inédite entre Réaumur. et Abraham Trembley. Geneva: Desclee de Brouvier

- Wikipedia. “René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9AntoineFerchaultdeR%C3%A9aumur