Search

Regions

Pierre Charlevoix

1722

Eighteenth century New France was visited by some famous Frenchmen. One of the most prominent was Pierre Francois-Xavier de Charlevoix (1682-1761). Charlevoix was a Jesuit priest, teacher and author. He visited New France twice, the first, a short visit to teach at the Jesuit college in Quebec between 1705 and 1708.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre-Fran%C3%A7ois-XavierdeCharlevoix

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre-Fran%C3%A7ois-XavierdeCharlevoix

Charlevoix returned to Quebec in September 1720. He first visited Acadia then from March, 1721 he set out from Quebec on a fact-finding tour of New France which included a mandate to look for the mythical Inland Sea. Travelling up the St. Lawrence he arrived in Montreal on March 15. Based in Montreal Chalevoix spent the next two months visiting French settlements at Fort Chambly, le Sault-Saint-Louis (Kahnawake) and Fort Frontenac (Kingston). He then set out on his expedition up the St. Lawrence to Lake Ontario, visited Niagara, and traversed the Great Lakes as far as Michilimachinac, near present-day Sault-Ste-Marie.

He then followed the Illinois River to the Mississippi. He travelled downriver, arriving at New Orleans in January, 1722. He was not impressed describing the town as “a hundred or so shacks”. Charlevoix left New Orleans intending to return to Quebec but his plans were interrupted by shipwreck. He eventually arrived back in France in December, 1722.

Charlemoix’s accounts were written up in a series of letters in his Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle France, avec le Journal historique d’un voyage fait par ordre du roi dans l’Amérique septentrionnale finally published in 1744.

Of greatest interest to Canadian ornithology is his Letter IX, in Volume 3, dated at Chambly, April 1st, 1722. In this letter he discusses fish, birds, mammals and plants noted in Canada. He particularly notes those “which are not without merit, and which are peculiar to America.”. It seems likely, although the letter is dated April 1st, the letter is probably a summary of observations that made an impression during he whole of his visit to New France. The section on bids covers pages 155-158.

Charlevoix may have had a reputation as a gifted botanist but an ornithologist he was not. This is evident in many of his comments on the birds he writes about. He mentions two sorts of Eagles one of which is clearly the Bald Eagle but the description of the second is so poorly rendered it impossible to identify. He mentions three species of hawks, not unidentifiable by name, and a fourth, clearly an Osprey “qui le vivent que de la Peche”. He mentions Canada Geese, Wood Ducks and references other ducks, shorebirds and field birds but provides little details.

His comments on Canada’s woodpeckers are also of little value:

Our woodpeckers are of extreme beauty; there are some of all manner of colours, and others quite black, or of a dark brown all over the body, except the head and neck, which are of a beautiful red.

It is clear from his description of three species of “partridges” and a few other species that Charlevoix copied extensively from the writings of well-known Acadian naturalist, Nicolas Denys’ Description of the Natural History of the Coasts of North America originally published in 1672. In this case and in other writings about species he merely provides details supplied by others and offer little that is new. As many naturalists had done before him, he was captivated by the Ruby-throated Hummingbird providing extensive notes.

Chalevoix states that the owl of Canada (Great Horned Owl) “differs from that of France by its white throat and a peculiar call” and then repeats Denys fable about it breaking the legs of field mice and storing and feeding them until they’re needed.

Despite the limited value in Charlevoix’s ornithological writings, two of his observations provide useful new information on Canadian species:

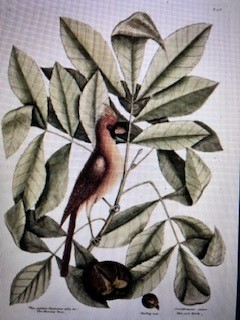

Northern Cardinal

Charlevoix’s comments on the range of the Northern Cardinal in the 1720s and its popularity in France are of considerable interest:

You must travel a hundred leagues to the southward of this place before you meet with any of the birds called cardinals. There are some in Paris which have been brought hither from Louisiana, and I think they might thrive in France, could they breed like the canary bird; the sweetness of their song, the brilliancy of their plumage, which is of a shining scarlet incarnate; the little tuft on their heads, and which in no bad resemblance to the crowns that painters give to Indian and American kings, seem to promise them the empire of the airy tribe.

The Red Bird. Catesby Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahamas Vol 1, Page 38

The Red Bird. Catesby Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahamas Vol 1, Page 38

Sandhill and Whooping Crane

The pre-European range of these birds in North America is subject to considerable uncertainty. It is not always clear in the writings of the early naturalists of New France that they were experienced enough to distinguish between a heron and a crane. This is despite the fact that they may well have been able to distinguish between the European Gray heron and Common Crane.

For a discussion of these species which I inadvertly left out of my draft paper on Charlevoix I attach correspondence from Michael Gosselin who reviewed it said that: "An important point that I find missing is the fact the Charlevoix, in his Chamby letter, refers to two species of cranes:"

"Nous avons des Gruës de deux couleurs ; les unes sont toutes blanches ; les autres d'un gris de lin. Toutes font d'excellens Potages."

Michel speculates that “It may be the earliest account where Whooping Cranes and Sandhill Cranes are distinguished”. Despite the fact that Charlevoix provides no description Michel thinks that these are genuine references to cranes rather superficially look-alike herons such as the Great Blue heron and American Egret. He also draws this conclusion based on the well-known fact that herons were notoriously unpalitable. Large herons like the Great Blue (and cormorants) are fish eaters whereas the flesh of cranes, which eat mostly small mammals, insects and vegetable matter, are much better eating.

As pointed out in the Charlevoix letter, it is not certain where the indigenous people were putting cranes into their soups. Charlevoix’s late spring and summer exploration extended as far west as Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. This area may well have been within the breeding range of both cranes in the 18th century. It would seen less likely that his references refer to the Richelieu Valley of southern Quebec.

The rise to prominence of the first naturalists, who had a strong interest in all branches of natural history, was typified in France by Rene Antoine Ferchault de Reaumur. Commenced in the 1730s his outstanding scientific collections, assembled from around the world. Michel Sarrazin, Medicin du Roi of New France, who demonstrated an interest in natural history, particularly mammals, died in.1735. Two bird specimens have been identified in the Reaumur collection sent by Sarrazin, a woodpecker either Black-backed or Pileated and a male Scarlet Tanager. These were noted by curator Jean-Etienne Guettard,. In 1740 he was replaced by Jean-François Gaultier. In the 1740s and 1750s, Gaultier, working with Guettard, sent a considerable number of bird specimens form New France.

The bird specimens in the Reaumur collection provided the basis for Brisson’s pioneering work, Ornithologie, published in 1760. Separate papers on Sarrazin, Reaumur, Guettard, Gaultier and Brisson will be fond elsewhere in this section.

Bibliography

- Catesby, Mark. 1729-1732. Catesby Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahamas 2 Vols. London : Mark Catesby

- Charlevoix, Pierre-François-Xavier de. 1744. Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle France, avec le Journal historique d’un voyage fait par ordre du roi dans l’Amérique septentrionnale. 3 Vol. Paris: Chez Rolin Fils

- Denys, Nicolas. Ganong edit. 1908. Description of the Natural History of the Coasts of North America. Toronto: The Champlain Society

- Guettard, Jean-etienne. Undated Partial Inventory of the Cabinet of Rene Antoine Ferchault de Reaumur MS1929. Paris: Museum of Natural History.

- Hayne, David M. 2003. “Charlevoix, Pierre-François-Xavier De” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 3. Toronto and Quebec: University of Toronto/Université Laval.