Search

Regions

Bachelot de la Pylaie

Expeditions to Newfoundland: 1816 and 1819-20

Introduction

The island of Newfoundland is located in high latitudes of eastern North America. The geography is dominated by glaciation which results in a rocky landscape, small lakes, peat bogs and boreal forest underlayed by poor glacial till soil. For centuries Newfoundland’s economy depended on its primary industries especially the cod fishery centred on the Grand Banks. French fishermen from Brittany are known to have seasonally visited Trepassey as early as 1505. By the end of the 16th century European fishermen were operating seasonally from coastal ports around the island and north to southern Labrador.

From the 17th century Newfoundland seasonal visitors were joined by the first permanent French and British settlers. Between 1662 and 1713 the administrative centre of French activity on the island was Plaisance (Placentia), on the southwest coast of the Avalon peninsula. French fishing settlements were scattered about the island. British interests were centred on the eastern Avalon and to the north in Conception and Trinity Bays.

After frequent European wars, France ceded its Newfoundland claim to Britain, set down in 1713 in the Treaty of Utrecht. Under this Treaty France retained possession of the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon off the south coast, and the rights of French residents to fish for cod on the “French Shore.” The French Shore included much of the south, west and north-east coasts of Newfoundland.

The hard and tenuous existence of living in Newfoundland did not lend itself to cultural pursuits. Prior to the early 19th century Newfoundland did not attract permanent residents who had the educational background or the leisure to research or write about the island's bird life. As a result what we know about Newfoundland ornithology is largely the result of the Banks expedition to the province in 1766 and the writings of one exceptional character, George Cartwright, who lived in southeast Labrador between 1770-1786.

Bill Montevecchi in his book Newfoundland Birds: Exploitation, Study, Conservation has written a detailed history of the development of the ornithology of Newfoundland and Labrador. At the time Montevecchi wrote his book, published in 1987, he was not aware of French scientific explorations to Newfoundland early in the 19th century. Unpublished manuscripts from these explorations were discovered by the late Ronald Rompkey of Memorial University of Newfoundland (MUN) while looking for Newfoundland material in French archival documents in Paris. In 2004 Dr. Rompkey published in French: Terre-Neuve, Anthologie des voyageurs français, 1814-1914. In this book he mentions the early Newfoundland voyages of Bachelot de la Pylaie and the fact that he collected natural history specimens including birds. This paper examines in detail the records of these expeditions.

Bachelot de la Pylaie

Since the mid-18th century France had been a key centre of natural history and ornithological research in Europe. Outstanding naturalists of the day included Methurin Jacques Brisson, Baron Buffon and Georges Cuvier. Brisson wrote Ornithologie in 1760. It contained dozens of descriptions of birds collected in New France. Unfortunately no birds were collected, described or sent to France from French possessions in Newfoundland.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the new French government decided to include naturalists in state-sponsored voyages of exploration. They were undertaken to assess the natural resources of France's possessions and territories. This policy lead to two small scientific expeditions to Newfoundland in 1816 and 1819-20, led by naturalist Bachelot de la Pylaie.

Auguste-Jean-Marie Bachelot de la Pylaie (1786-1856) was born into a wealthy family at Fougères, a town northeast of Rennes, in Brittany. He was the son of René-Roch-Pierre Bachelot de la Pilaie and Claire-Renée-Geneviève Vigeon, dame du Plessix. Bachelot trained as a lithographer but from an early age showed a strong interest in natural history.

About 1810 Bachelot came to the Museum of Natural History at the Jardins des Plantes in Paris to study with two of the most important French naturalists of the period: Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) and Henri-Ducrotay de Blainville (1777-1850).

On Cuvier's recommendation Bachelot was selected to undertake the natural history survey of France’s Newfoundland possessions. By the time of his appointment Bachelot had developed into a highly trained biologist. His subsequent career suggests that he was primarily interested in botany, marine zoology and archaeology. His noted work on Newfoundland natural history is his Essai sur la Flore de Terre-Neuve et des Iles St. Pierre et Miclon, an unpublished manuscript, written in 1829.

Fortunately for Canadian ornithology, Bachelot, professionally-trained by Cuvier and de Blainville, also collected and scientifically described birds and other zoological specimens during his expeditions. In particular, his unpublished sketchbook (MS 1798) from his first expedition in 1816, and two notebooks, Voyage à Terre-Neuve (MS 1800) and Voyage L’Isle de Terre-Neuve (MS 1801), from the 1819-20 expedition, provide considerable information on the birds he encountered. These manuscripts, housed in the Natural History Museum Library in Paris, also contain details on plants, mammals, fish, crustaceans and insects.

This paper examines the ornithological results from Bachelot’s two expeditions. These can be seen in Table 1: Birds Collected in Newfoundland and the French Islands by Bachelot de la Pylaie in 1816 and 1819-20. Bachelot’s bird records are extensive and scientifically important to our understanding of early Newfoundland ornithology. The details of various common and scientific names used by Bachelot, along with details of records, manuscript references and notes in Table 1are intended to provide background information on many species discussed in this paper.

Bachelot's bird collection, which contains 152 records, was largely made up of an assortment of confusing, similar-looking species associated with the Newfoundland littoral: diving ducks, scoters, mergansers, alcids, gulls, pelagics and shorebirds. He also collected and described a few land birds including ptarmigan, three owl species, corvids, thrushes, finches, sparrows and warblers. In 1820 ornithology as a discipline was beginning to enter the age of professionalism. Bachelot's descriptions were written when species scientific names were in a state of flux due to the evolving understanding of genus and family and seasonal and gender changes in plumage were poorly understood.

Despite these difficulties it is possible to identify many species by their names on bird lists Bachelot sent to France, and others by scientific descriptions, where common and scientific names are inadequate. At this point it is important to recognize the contribution of Michel Gosselin, formerly curator of the ornithology collection at the Canadian Museum of Nature. Working with my cellphone images photographed from pages in Bachelot’s notebooks, he was able to decipher the French text and identify the great majority of the birds described. There is no doubt that, without Michel’s contribution, bringing together Bachelot’s bird records with scientific accuracy would not have been possible. Any errors that may be found in this paper are entirely my responsibility.

The 1816 Expedition

Bachelot's first visited Newfoundland in 1816 aboard the frigate, Cybelle. He departed Brest in Brittany on June 3, 1816. He arrived at Croc (Croque), a small French fishing village on the east coast of the Great Northern Peninsula on June 18th. After a brief stay he sailed to the French administrative capital on the island of St. Pierre. Bachelot returned to Croque on July 10th. Sometime during his absence from Croque, Bachelot mentions that he collected pelagic species on the Grand Banks and visited the community of Colinet, St. Mary's Bay, in the southern Avalon. On August 5th Bachelot left the French settlements in the Northern Peninsula to explore the Strait of Belle Isle. After a few days cruising the Labrador coast, he crossed the Strait to Quirpon on the northern tip of the peninsula. He arrived back at Conche on August 12th. After one and a half months in the area Bachelot left for Europe on October 1st. After a brief stay in the Azores, he arrived at Brest in late October.

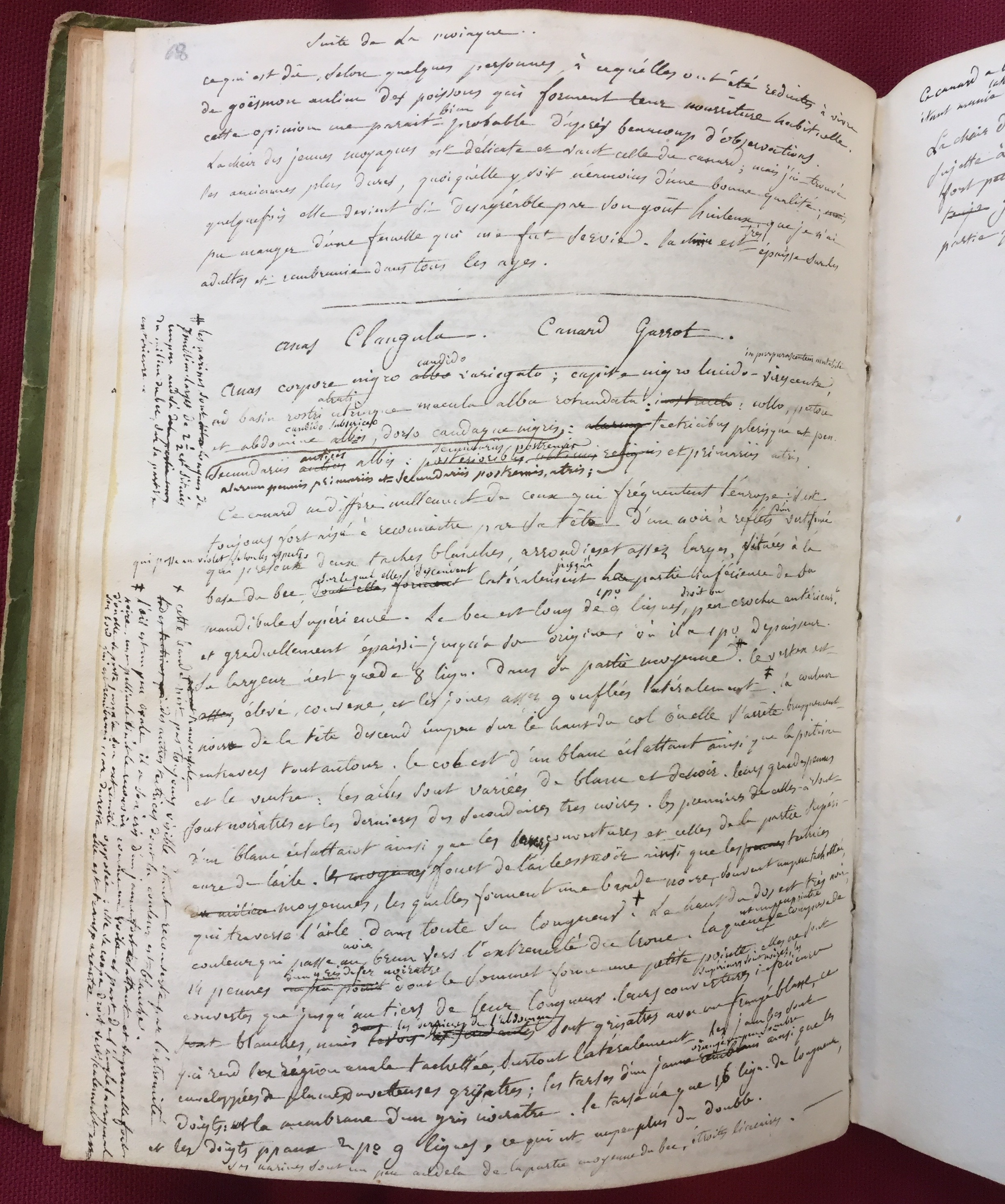

The content of Bachelot's 1816 bird records consist of eleven attractive pencil sketches of the heads of birds that he collected, and a few accompanying notes, including brief descriptions of the Eskimo Curlew and Northern Fulmar and a detailed scientific description of a Black-capped Chickadee. Birds he drew included Willow Ptarmigan, Eskimo Curlew, Hudsonian Godwit, Common Murre, Black Guillemot, Atlantic Puffin, Common Tern, a Storm-Petrel species, Northern Fulmar, Great Shearwater and American Robin. All sketches were of bird’s heads except for the American Robin which is illustrated in its entirety above.

The Sketchbook contains other natural history artwork of species he encountered or collected, including botanical specimens and marine life, perhaps foreshadowing his future career interests.

The first artwork, rendering images of Newfoundland birds, was illustrated by Eleazar Albin in 1738, and George Edwards in 1747 and 1750. A few birds collected by Joseph Banks, ascribed to Newfoundland or Labrador, were painted by Charles Collins, Pierre Paillou and Sydney Parkinson. Some appeared in Thomas Pennant’s Arctic Zoology in the 1780s and 1790s.

Bachelot's sketches are the first by a visitor to Newfoundland who collected and illustrated his own ornithological specimens. While the sketches from the 1816 trip were not extensive, they are of sufficient quality to allow for easy identification. Sketches of the Common Tern, Northern Fulmar and Great Shearwater provide the only records for these three species from the Bachelot expeditions.

Since the 1816 expedition was almost exclusively conducted in Newfoundland waters, the three represent the first time these birds were recorded as present in Newfoundland. Bachelot wrote only one scientific description from his 1816 expedition. His Black-capped Chickadee, originally described by Banks, was not recorded or described on the second expedition.

In total Bachelot’s four records from 1816 were unique contributions to the total of sixty-one species identified from the two expeditions. They are included in the full list of 152 bird records set out in Table 1 and identified by an “S” for sketch.

The 1819-20 Expedition

Identifying the birds either listed and/or described on the second expedition from Bachelot’s notebooks has proved considerably more challenging. In addition to issues with identifying bird names on two bird lists sent to France, the difficulty in identifying birds from Bachelot's written descriptions is manifold. Bachelot regularly used both common and contemporary scientific names to identify the birds he listed or described. Normally these names might positively assist identification. Unfortunately he often failed to recognize that immature birds and adult male and female specimens might be the same species so he ascribed them different common and scientific names. In some cases he also failed to appreciate that long-lived birds such as gulls could go through multiple year plumage changes before attaining adult plumage. In most but not all cases he understood that adult diving ducks and alcids had different plumages in summer and winter.

In 1819 Bachelot sailed in the corvette, Espérance on his second, more comprehensive scientific exploration of Newfoundland. This ship appears to have been captained by Hyacinthe de Bougainville, son of the famous French explorer, Antoine de Bougainville. Later, between 1824 and 1826, Hyacinthe de Bougainville was a key member of France's around-the-world expedition in the vessels Thétis and Espérance. The main purpose of that voyage was to enhance French diplomatic relations in Indochina.

The sailing date of Bachelot's second voyage to Newfoundland is not known. He tells us in a fourth manuscript, Voyage a l'île de Terre-Neuve (Manuscript VV 104:24225), that he was in Miquelon in October, 1819, but he probably sailed from France in the late spring. Before wintering in St. Pierre, he explored west to Bay d'Espoir and L’anse aux Coudriers along the south coast of Newfoundland with pilot, M. Briant. On this trip he appears to have mostly collected lichens. In addition to revealing the partial expedition itinerary, this manuscript contains extensive notes on climate, weather, and general observations on other fauna, including insects.

Bachelot is known to be in Miquelon in May, 1820. In late June he set out in the corvette L'Active for Bay St-Georges on the west coast of Newfoundland. It is interesting to note that thirteen years later (1833) Bay St-Georges was Audubon’s prime area for collecting birds in the Colony. Bachelot notes that his captain, M. Robillard, was largely responsible for collecting birds and insects in the area while he collected plants.

Bachelot spent about 6 weeks collecting in the Bay St. Georges area before sailing north on August 19th. After brief visits to the settlements of Ingornachoix (Port-aux-Choix), Keppel Island and nearby Port Saunders, he arrived at Quirpon on August 29th. After a short visit, he sailed to Croque in early September. Bachelot collected in the Croque, Conche and Hare Bay area until late October when he sailed for France in La Levant.

Bachelot never returned to Newfoundland. In 1826 he carried out scientific research on the islands of Hoedic and Houat off the coast of Brittany. Today Bachelot was primarily known for his study of the archaeology of Brittany. He died in 1856.

As noted earlier, Bachelot left numerous unpublished notebooks (MS1800 and MS1801) from his second Newfoundland expedition. They contain detailed descriptions of many birds, mammals and marine life he collected. While his script is very small, and not always easy to read, his writings contain many of the first scientific descriptions of Newfoundland birds. MS1800 essentially covers the year 1819 and MS1801 the year 1820. His bird list in Table 1 which is arranged in AOS Checklist order, includes his artwork, and all the common and scientific names he used in his lists and scientific descriptions.

Fifty-four additional species were collected and described from the 1819-20 expedition. His detailed ornithological descriptions are the first by a naturalist who visited Newfoundland since Joseph Banks. In addition six detailed descriptions have been identified as either seasonal or gender plumage variations of previously described species. Five detailed descriptions can only be identified to genus level: a calidris sandpiper, a jaeger, a gull, a storm-petrel species and a waxwing.

Bachelot's notebooks also contain two lists of bird skins he sent to France. The first list (MS1800:163) was sent on October 10, 1819. It contains 39 skins representing about 20 identifiable species. Included in this list are the expedition’s only records for Brant, Snowy Owl and Northern Flicker. No descriptions have been found for these birds. They bring the second expedition total to 57 species.

Unfortunately some skins on the list have incomplete scientific names and/or descriptions and remain unidentifiable. It is not possible to be certain where these birds were collected. At this time it is unknown where the expedition spent the first summer.

The second list (MS1801:148) was sent of June 15, 1820. It contains twenty-nine bird skins representing about 12 species. The 1820 specimens were collected by M. Mariadet (14 skins) and M. Blanchet (15 skins). Blanchet also collected 5 mammals’ skins: Red Fox and Pine Marten as well as skins of an unidentified mammal, a weasel and a seal. Given the fact that Bachelot left St. Pierre in late June, 1820, it seems likely that Mariadet and Blanchet were residing in St. Pierre or Miquelon at that time, and that all the specimens, all likely winter residents, were collected there. All of the listed identifiable bird species described elsewhere may have been from Newfoundland.

A few pages contain references to nests of six species of birds: Common Eider, Common Murre, Atlantic Puffin, Bald Eagle, Common Raven and an unidentified gull species. Bachelot also collected eggs from murre, puffin and eagle nests as well as from an unidentified cormorant. The eggs from a storm-petrel nest MS1800:94 offers conclusive proof that the associated description of a storm-petrel is a Leach’s Storm-Petrel. These records are all from MS1800 which was known to have been written in 1819. Given traditional nesting and egg laying dates in Newfoundland, one can assume they were likely collected in July, 1819. Since the expedition route in 1820 travelled in a clockwise direction west from St. Pierre, one can speculate that the nests and eggs were collected either from the Northern Peninsula or the French shore of the southern Avalon which extended west from Trepassey to St. Pierre and Miquelon and included St. Mays Bay and Pacentia Bay.

In total the number of species recorded by the two expeditions is sixty-one: 1816 (4) and 1819-20 (57).

The Significance of Bachelot's Ornithological Records

The tradition of important unpublished early Canadian ornithological records highlighted throughout this website is amply demonstrated in he works of Bachelot de la Pylaie. In this case the record is muddled by the fact that in some cases it is not possible to know if his birds were collected on the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon or on mainland Newfoundland. Since his records were never published his contribution to first record status is debatable.

Many Canadian waterfowl, seabird and boreal forest birds had already been scientifically described in the 18th century from the Banks material and from the collections assembled by the Hudson’s Bay naturalists and described by George Edwards, Carl Linnaeus, Reinhold Forster, Thomas Pennant and others.

Despite the fact that by 1820 so much was already known about the Canadian avifauna, the Bachelot manuscripts add significantly to our knowledge of the birds of Colony of Newfoundland, now the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. All sixty-one identifiable bird species are from the French islands and insular Newfoundland.

Based on an examination of 18th century bird records from the province twenty-one birds observed or collected by the Bachelot expeditions appear to be first records of occurrence in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador and on the island of Newfoundland. Provincial records include:

- Brant

- Common Goldeneye

- Purple Sandpiper

- Dovekie

- Common Murre

- Razorbill

- Herring Gull

- Iceland Gull

- Common Tern

- Northern Fulmar

- Great Shearwater

- Double-crested Cormorant

- Great Cormorant

- Great Horned Owl

- Snowy Owl

- Tree Swallow

- Boreal Chickadee

- Common Redpoll

- Red Crossbill

- Lapland Longspur

- Henslow’s Sparrow

In addition, ten species, previously recorded by Banks in Labrador, are first records of occurrence on the island of Newfoundland:

- Black Scoter

- Semipalmated Plover

- Eskimo Curlew

- Short-billed Dowitcher

- Wilson’s Snipe

- Greater Yellowlegs

- Great back-backed Gull

- Red-throated Loon

- Horned Lark

- Snow Bunting

Readers who know Newfoundland birds will note the presence of some very common provincial birds. The fact that no earlier records have been found to date reflects the paucity of records up until the time of this expedition. Hopefully further examination of the expedition records will assist in improving them. This may result in assigning some to the French Islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon.

The Henslow’s Sparrow record from St. Pierre and Miquelon deserves further attention by ornithologists. It was identified by ornithologist Michel Gosselin. Michel will write a paper on the details of this very significant record. It is the most important ornithological record from the two expeditions.

Further research on Bachelot de la Pylaie at the Library of the Natural History Museum in Paris may uncover more details of his natural history writings from his two trips to Newfoundland. The important legacy of Bachelot’s expeditions is evident in his attractive artwork, his extensive manuscript notes of scientific quality, and his Essai sur la Flore de Terre-Neuve et des Iles St. Pierre et Miclon. Publishing a book or books detailing all Bachelot’s natural history records from his expeditions would be very significant event in the history of Canadian natural history.

Bibliography

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration, Wikipedia Reference http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EuropeanandAmericanvoyagesofscientificexploration#1824.E2.80.931826:LeTh.C3.A9tisandL.27Esp.C3.A9rance

- Forster, Reinhold 1777.

- Montevecchi, William 1987. Newfoundland Birds: Exploitation, Study, Conservation. Cambridge Mass: Nuttall Ornithological Club

- Pennant, Thomas 1784, 1875. Arctic Zoology. 2 Vols. London: Henry Hughs

- Pylaie, Bachelot de la. 1816. MS 1798, Sketchbook. Unpublished Manuscript. Paris: Natural History Museum

- Pylaie, Bachelot de la. 1820. Voyage à Terre-Neuve (MS 1800). Unpublished Manuscript. Paris: Natural History Museum

- Pylaie, Bachelot de la. 1820. Voyage à L’Isle de Terre-Neuve (MS 1801). Unpublished Manuscript. Paris: Natural History Museum

- Pylaie, Bachelot de la. MS 1800, 1801. Voyage aux Iles de Terre-Neuve 1819-20. Unpublished Manuscripts. Paris: Natural History Museum

- Pylaie, Bachelot de la. 1802. Manuscript VV 104:24225, Voyage à L'île de Terre-Neuve. Unpublished Manuscript. Paris: Natural History Museum

- Pylaie, Bachelot de la. 1829. Essai sur la Flore de Terre-Neuve et des Iles St. Pierre et Miclon. Unpublished Manuscript. Paris: Natural History Museum

- Rompkey, Ronald. 2004. Terre-Neuve, Anthologie des voyageurs français, 1814-1914. Rennes, France: Rennes University Press

![American Robin: Merle de T[erre] N[euve]](american-robin.png)