Search

Regions

Joeseph Banks

Introduction

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) was heir to a great fortune which included Revesby Abby, an estate in Lincolnshire. Banks attended Harrow and Eton where he acquired a passionate interest in natural history, particularly botany. After graduating from Cambridge, Banks devoted his life to natural history and scientific pursuits.

When his father died in 1761 his mother purchased a house close to the Chelsea Physic Garden. There young Banks was introduced to head gardener, Phillip Miller, one of Britain’s most knowledgeable botanists. Miller taught the young Banks the fundamentals of modern botanical methods of identification and collection, and garden management. Miller was widely known in the European botanical community and was a close friend of Carl Linnaeus. As a wealthy gentleman of leisure interested in natural history, Banks soon became a major collector of natural history books, manuscripts, drawings and collections.

It is likely that the publication of Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of of Carolina, Florida and the Bahamas (1729, 1731, 1743) and the works of George Edwards published between 1743-1764, would have been an inspiration. The North American botanical travels of Per Kalm and the huge traffic in plant material between avid gardeners such as Peter Collinson and Dr. John Fothergill in England and naturalists in America may also had a significant influence.

It is not known why Banks chose Newfoundland and Labrador for his first scientific expedition. Averil Lysaght in her seminal work of Banks’s trip to Newfoundland Joseph Banks in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1766, speculates it may well have been a combination of circumstances. During the Seven Years War New France fell into the possession of Britain. The territory was officially handed over with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763 and a Governor was appointed for Newfoundland and Labrador. Britain was interested in investigating the potential of Labrador which was largely unpopulated and its economic potential unknown.

This paper is basically a summary of Lysaght’s outstanding work of scholarship. I suspect that however careful I have been to faithfully condense her work in this paper errors are inevitable. All readers interested in early Canadian ornithological history should have a copy of her seminal work.

In the early 1760s the Moravian Church, based in Germany, sought and received the approval of the British government to carry out missionary work in Labrador. From the early 1760s Lysaght notes that Banks was receiving botanical material from them. He would also have been familiar with the Physic Garden’s collection of North American plants. Banks was also a close personal friend of John Montagu, Fourth Earl of Sandwich (1718-1792) who made his career in the Admiralty. Montagu may well have arranged passage for Banks and his friend, naval officer, Constantine John Phipps, on the 32 gun frigate, H.M.S. Niger, on its annual provisioning trip to Newfoundland, and Labrador.

The Exploration of Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766

Banks’ detailed preparations for collecting botanical and zoological specimens are a clear indication that he was planning a serious scientific expedition. He drew heavily on the advice of his friends Daniel Solander, who had visited Lapland, and John Ellis who had visited the West Indies. In his cramped Niger cabin Banks kept a small library with the works of Catesby, Edwards and Linnaeus. He also brought notebooks and paper for recording, a collection of guns for shooting birds, plant presses, butterfly and fish nets, and many glass rounds, wooden casks (barrels) and kegs (small casks) for preserving animal specimens. Harold Carter in his biography of Banks Sir Joseph Banks 1743-1820 (p.33) noted “With him he carried an array of written questions from Thomas Pennant, primarily devoted to animals and birds he might encounter.” Banks also brought along help in the form of his servant, Peter Briscoe, who acted as his assistant.

Painting of Sir Joseph Banks: The Natural History Museum

Painting of Sir Joseph Banks: The Natural History Museum

The Niger left Plymouth on April 11, 1766 and reached St. John’s exactly one month later. Banks and his friends spent one month collecting around St. John’s. Unless the weather was too severe Banks went out daily with his gun to collect birds, mammals, insects and plants.

The most important written documents that have survived his expedition are his Diary, now found in the Adelaide (South Australia) Archive, and a manuscript related to birds in the Rare Book Library at McGill University. The latter contains 41 slips of paper in Banks’s handwriting with descriptions of birds plumage and measurements of body length and wing size, habitat, and place of collection written in Latin, and identified by Linnean binomial nomenclature. Each description is accompanied by a Diary reference and keg reference in which the specimens were stored.

In the St. John’s area, as the spring advanced Banks is known to have collected a Barn Swallow and a Wilson’s Warbler.

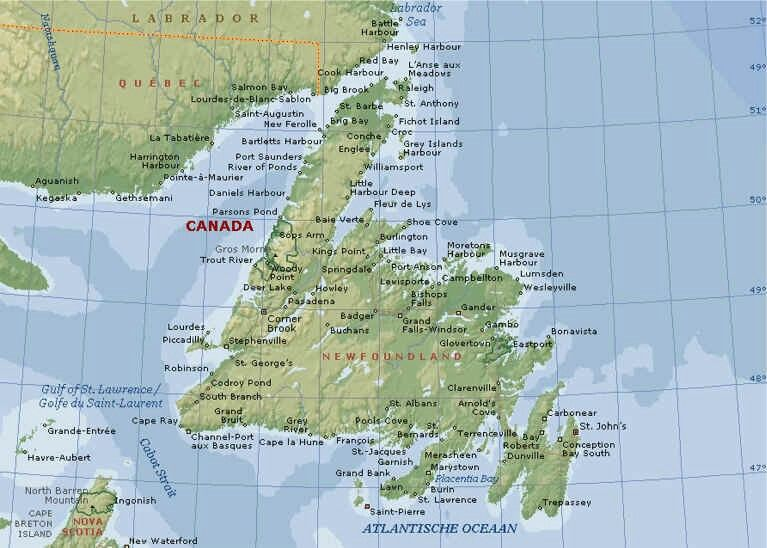

The Niger arrived at Croque on the east coast of the Great Northern Peninsula on June 11. Banks collected in the immediate area for one week. He wrote about the birds he collected there in his diary with reference to his detailed descriptions (Banks:126):

Today shot a beautiful kind of kingfisher Acedo Alcyon [Belted Kingfisher] figurd by Catesby & Edwards Linnaeus’ description of it seemed Faulty in many Parts No:12 I took great pains to make as Particular as Possible a Kind of Bird which seems to belong to the Butcher Bird tribe, Lanius? [Northern Shrike] but I cannot find that he is described No:13 also another Small Bird Motacilla No: 14 [Swainson’s Thrush] who sings agreeably enough

The Niger left Croque on June 22. It sailed south to Conche on July 11. Banks became seriously ill with fever. He lay in his cabin virtually the whole time doing little collecting at this location.

Sufficiently recovered, Banks sailed north in Niger on August 6. He crossed over the Strait of Belle Isle to southeastern Labrador arriving at Chatteaux Bay, Labrador, on August 10th. Chatteaux Bay, now spelled Chateau Bay, just south of Henley Harbour, was the site of the recently constructed Fort York. Banks collected many of his specimens in the Chatteaux Bay area. He left Chatteaux Bay on October 3rd. He returned to Croque for a few days before sailing for St. John’s. The Niger sailed for England in late October.

During Banks’ return visit to St. John’s he may have met Captain James Cook who had just completed survey work on the south coast. Cook was visiting St. John’s before returning to London at the end of his hydrographic season. Banks was gifted an Aboriginal canoe from Governor Palliser which was placed on Cook’s survey vessel the Grenville (Hough :49) for transportation back to London.

Cook spent almost ten years on the east coast of Canada between 1758 and 1767. He participated in the final siege of Louisbourg in 1758, charted parts of the Gaspe and the St. Lawrence River in preparation for the invasion of Quebec. Between 1763 to 1767 Cook charted the island of Newfoundland providing such quality maps that they were used into the 20th century.

Unfortunately Banks did not publish the results of his collecting before leaving on the first Cook Expedition in 1768, and did not complete it on his return. In fact, despite his many accomplishments, Banks published very little. It appears he preferred to allow others to publish using his notebooks and specimens concentrating instead on working behind the scenes to use his formidable wealth and impeccable connections to promote the natural sciences to commercial interests and government at every opportunity.

Banks arranged for many of his specimens to be painted by the artist, Sydney Parkinson. As early as 1768 he freely loaned his specimens, paintings, diary and manuscripts to collector Taylor White and author Thomas Pennant. Pennant was planning a book on North American zoology. White first commissioned Charles Collins to paint his birds. After Collins died White and Pennant both hired artist Pierre Paillou to paint many of Banks’ specimens. Pennant never completed his zoology at that time. In the interim Pennant had prepared a species list which was included by J. Reinhold Forster in his A Catalogue of the Animals of North America published in 1771. The historical record reveals that Pennant was clearly more important than White in providing secondary support for assessing Banks’s Newfoundland and Labrador records. A few notes on both are provided at the end of this paper.

Banks’ bird records with the Paillou and Parkinson paintings were eventually published in John Latham’s General Synopsis of Birds (1781-1802) and Pennant finally published Arctic Zoology (1784-87). Johann Frederich Gmelin, editor of the 13th Edition of Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae also published material from Forster, Pennant and Latham.

Due to poor preservation techniques at this time and the wide displacement of his specimens, documents and paintings to fellow ornithologists, not all of Banks’s very significant collection was identified and published at the time. Lysaght’s piecing together of the Banks material clearly shows that several of Banks specimens were the “types” for new species described by others.

Species collected by Banks which were the basis of the first descriptions of North American birds include:

- Green-winged Teal

- Labrador Duck

- Rough-legged Hawk

- Northern Goshawk

- Greater Yellowlegs

Overview of the Ornithological Results of the Banks Expedition

The Banks Expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador was the most important single Canadian ornithological event of the18th Century. Two other key 18th century events covering early collecting in New France and in Hudson Bay will be found under New France 1700-1760, and under 18th Century Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba respectively.

Brisson’s Ornithologie, published in 1760, contains over 40 scientific descriptions from New France collected in Quebec. The ornithological records of 18th Hudson Bay employees in three provinces, skillfully compiled by Stuart Houston, was published in 2003 in his pioneering work Eighteenth-Century Naturalist of Hudson Bay.

Lysaght’s superior scholarship is evident in her book, published in 1971, in which she pieced together, from many disparate sources, the bird records of Banks’ expedition. It is clear that Banks’ trip was primary botanical, however Lysaght’s analysis of bird records, and additional work by Bill Montevecchi in his Newfoundland Birds reveals that Banks collected or observed 76 species. These species are all well documented, mostly from two sections of Lysaght’s book:

- Descriptions in Latin of Birds and Insects, with Notes and English Translations p. 351-392. (The McGill Manuscript)

- A systematic list of the animals collected or recorded by Banks in 1766; Section on Birds p. 407-420

To date, Lysaght’s book is not available through the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Banks’s description of the Savannah Sparrow, collected in Newfoundland, is one of only four written in English, (the rest written in Latin and transcribed into English). An excerpt from the McGill Manuscript (Lysaght: 387) provides evidence of Banks’s scientific abilities:

[Keg] Reference: 19:3 No. 2

a Small Bird seems to belong to the Genus of Fringilla from the point of the Bill to the tip of the Claws 5 inches its wings Extended 9 inches the upper Mandible is Black the Lower Flesh Coloured inside of his mouth Flesh Colourd his Throat & Breast are white with Black Spots his Belly & rump white his legs & Toes are Light Brown his Claws a little Darker the under Part of his Tail & wings Light Brown the Top of his head Varies in small Spots with Black white & Brown the Pupils of his Eyes are Black over Each of them is a yellow line his Back is in Colour like the Top of his head his tail which Consists of ten feathers is Brown the two outside feathers being tipd with white.

The Savannah Sparrow was recorded by many naturalists, but a scientific description accepted by the AOU dates from 1789. Lysaght points out elsewhere that the measurement technique used by Banks required that all bird sizes recorded needed to be adjusted upwards due to the way the birds were measured.

Montevecchi’s Newfoundland Birds

Banks’s material was also examined by Bill Montevecchi and his team of researchers for Newfoundland Birds published in 1987. While acknowledging that his bird records are based primarily on Lysaght’s work, the Montevecchi list contains 91 species. A close reading of Montevecchi’s analysis of Lysaght’s research gives confidence that his analysis has been thorough and the species he adds to the Lysaght Banks list are, for the most part, appropriate.

Introduction to reconciling Lysaght and Montevecchi Bird Records

Discussed below is my analysis of Montevecchi’s and Lysaght’s comparative lists for Labrador and for Newfoundland as well as additional species unassigned to a location. The results of his analysis is shown in Table 1. List of Birds from Joseph Banks Expedition to Newfoundland Labrador in 1766. The accompanying text discusses the differences between Lysaght’s and Montevecchi’s analysis of the Banks bird records which are highlighted in Table 1.

I point out first of all that I have not included in the Table 1 five species listed by Montevecchi which he deems “of unidentified locality or less than positive identification”. The recording of super rarities Long-billed Curlew and Northern Cardinal in 1766 can be eliminated as highly improbable. Great Horned Owl, American Tree Sparrow and Palm Warbler are birds that could be recorded in province. The fact that they are listed without location, uncertain in identity by Lysaght and Montevecchi, and not listed by Pennant is sufficient for me to remove them.

Banks’s Newfoundland Birds

Montevecchi’s book is heavily focused on the birds of insular Newfoundland. In his detailed analysis of the Banks material he listed 34 species for the island. He discusses in detail the rationale for including all 34 species in a section entitled “Documentation of 34 Species of Birds of Insular Newfoundland”. I have removed “Shearwater species” as unidentifiable adjusting his total to 33. Included in his list of 33 is a Banks diary sight record of Atlantic Puffin not mentioned by Lysaght.

Lysaght’s Newfoundland list contains 40 species, including eight species not listed by Montevecchi. The species and her associated Joseph Banks page numbers which discuss each species are as follows: Surf Scoter (410), Red-breasted Merganser (410), Bald Eagle (412), Whimbrel (413), Semipalmated Sandpiper (415), Ring-billed Gull (416), Blue Jay (418) and White-throated Sparrow (420).

Lysaght’s detailed discussion of these birds, all common species in insular Newfoundland during the time of Banks’s visit, and either mentioned specifically by Pennant, or verified in other Lysaght documentation, seem acceptable for inclusion. Many are sight records which confirms their presence in the province but may account for Montevecchi’s reluctance to include them. Their inclusion brings the combined total of Lysaght-Montevecchi Banks Newfoundland records as shown in Table 1 to 41.

Most of the specimens collected by Banks are first records for the province. A few seabirds recorded and collected by Banks in Newfoundland or Labrador were previously described from insular Newfoundland by Albin (Common Loon) and Edwards (Long-tailed Duck, Red-breasted Merganser, Harlequin Duck and Great Auk).

Banks was known to have collected a Fox Sparrow, an iconic bird in Newfoundland, at Croque on October 7, 1766.

Banks’ Labrador Birds

Montevecchi’s original Labrador list contains 44 species which includes an unidentified eagle and jaeger. Removing these records reduces his total to 42. His list contains four species not specifically listed by Lysaght from Labrador. This analysis defers to Lysaght’s outstanding scholarship especially since Montevecchi’s area of research focus was insular Newfoundland. Removal of the four records reduces Montevecchi’s total to 38. Lysaght’s treatment of the four records are as follows:

- Long-tailed Duck: not recorded by Lysaght

- Red Phalarope: recorded by Lysaght but no location known

- Whimbrel: after extensive discussion Lysaght (p. 413) assigns this record to Newfoundland

- Fox Sparrow: recorded by Lysaght from Newfoundland but not Labrador.

Lysaght’s list contains 45 species, 38 common to Montevecchi plus seven additional species:

- Common Eider

- Hudsonian Godwit

- Sanderling

- White-rumped Sandpiper

- Bald Eagle

- Golden Eagle

- Short-eared Owl

Given the thorough nature of Lysaght’s scholarship, her detailed analysis of each species, and their likely occurrence in southeast Labrador in the season of Banks’s visit, I have accepted her complete list. This results in the Banks total for Labrador at 45 species.

An excerpt from the Banks Diary (p. 138) of September 1, 1766 at Chateau Bay provides some detail of Banks’s particular orientation to game birds so common in his day:

Birds here are of many sorts which as well as Every other natural Production I still Subjoin a Catalogue mentioning in this Place only those good for Food or some other way remarkable among the best of the First Sort is the Curlew who was mentioned before here are also 2 more species of it both very good Eating tho not so delicate as the first golden Plover too is here & feeds with the Curlew up Crowberries Ducks & Teal many sorts all the fresh water ones very good but those who inhabit Salt water the most fishy Birds I ever met with the wild geese here are just Coming in very Fat and Larger I think than Tame geese in England there are partridges also of two Kinds brown & white for so they Call those Distinguished by a white spot upon their wings they are like our heath fowl but near as Large as the Black game these are good to eat but Some birds there are that I must mention tho they have not that Excellence Particularly one Known here by the name of Whobby [Common Loon] he is of the Loon Kind & an Excellent Diver but very often amuses himself especially in the night by flying high in the air and making a very Loud & alarming noise at least to those who do not Know ...

The combined total Montevecchi and Lysaght records that can be assigned to either Newfoundland or Labrador or both as shown in Table 1 is 70 species.

Banks NL Birds Without Location Specified

The Lysaght record indicates six species collected by Banks where it is not possible to identify the location. The species are:

- American Black Duck

- Red Phalarope

- Glaucous Gull

- Leach’s Storm-Petrel

- Northern Flicker

- Yellow-rumped Warbler

Adding these species to the overall list brings the Banks total to 76.

Montevecchi lists eleven species unassigned as to location. Lysaght has assigned nine of these to either Newfoundland or Labrador. Two species Common Murre and Northern Gannet unassigned by Montevecchi are not listed by Lysaght. They are likely omissions which Banks almost certainly collected or observed. Pennant mentions the Gannet. As there is no written record in the Banks material, I have not included either in the expedition totals.

The decision to include or exclude records in the case of the Banks’s expedition has been particularly challenging. For the most part overall I have accepted Lysaght’s records for Newfoundland and Labrador and Montevecchi’s for Newfoundland. Hopefully with more research some of these records will be assigned to Newfoundland or Labrador or both.

Additional Details from the Taylor White Archive and Thomas Pennant’s Arctic Zoology

There are many interesting written accounts on species in the historical record. Lysaght’s documentation is particularly impressive. Some individual detail is provided below:

The Taylor White Archive

The Taylor White Archive at McGill University has an extensive collection of drawings of 18th Century natural history specimens. White, a wealthy British judge, commissioned over 900 drawings initially painted by Charles Collins (1680-1744) and after Collins’s death, by Peter Paillou (ca1720-ca1790). An examination of the Collection provides some additional insight into the Banks Collection.

Considerable scholarly research and published articles have been written on the White Collection which add considerable flavour to the importance of the collection and this era. Readers may find the following recent articles in “Undescrib’d: Taylor White’s ‘Paper Museum’” from the Royal Society’s Notes and Records Vol. 75:4 (2021) of interest:

- Ornithological Insights into Taylor White’s Birds

- ‘Obliging and Curious’: Taylor White (1701-1772) and his remarkable collections

From inscriptions of the backs of a few drawings is known that Banks gave at least four bird specimens to White that were painted by Paillou. These include: Black Guillemot, Rough-legged Hawk, Eskimo Curlew and Glaucous Gull. None of these records add new species or location of collection to the Banks expedition records.

The Glaucous Gull record is verified by records in the Taylor White McGill Archive. In addition to a painting by Peter Paillou, the script accompanying the painting notes:

This Bird is all White except the shafts of of \[sic\] the Feathers which are of a pale brown. The legs & feet Orange coloured the bill pale flesh colour the point Black it is of the size of a Goose. It was brought by Mr Banks from the Northern part of America. No 41.

Thomas Pennant’s Arctic Zoology

Unlike White, there is a considerable literature on British naturalist Thomas Pennant.

I have used references to Newfoundland and Labrador or the northwest Atlantic in Pennant’s Arctic Zoology as a source which offers an affirmation of Banks’s bird records.

A few examples, verified by both Lysaght and Montevecchi, are presented here with associated page numbers:

| Bird | Page | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Bald Eagle | 194 | “endures North America’s severest winters even as high as Newfoundland” |

| Short-eared Owl | 230 | “found in plenty in the woods near Chateau Bay on the Labrador coast” |

| Leach's Storm-Petrel | 536 | “found about the Atlantic” reference from Kalm I 22/23 |

A reference to the Leach’s Storm-Petrel can be found in the Banks Diary and thus an acceptable expedition record for Newfoundland and Labrador.

Other records in Arctic Zoology for various reasons Lysaght not accept. Montevecchi accepted the Gannet record but as mentioned earlier without documentation I have excluded it.

| Bird | Page | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Northern Gannet | 582 | “inhabits the coast of Newfoundland, where it breeds” |

| Bank Swallow | 430 | “inhabits Newfoundland in the summer” |

| Razorbill | 510 | “inhabits the coast of Labrador in summer” Associated with the text is a comment from Pennant that his specimen and notes was received from Peter Simon Pallas who got it from a Moravian missionary |

| Dovekie | 512 | “it is called in Newfoundland the Ice-bird, being the harbinger of ice” |

It is likely that Pennant, who was remarkably well-connected in many circles which could provide him with records obtained information from Banks, George Cartwright or Moravian missionaries. In addition to sending material to German ornithologist, Peer Simon Pallas, Moravian missionaries were also known to have passed on bird specimens to Banks. Further research may eventually turn up a few new bird records for the province.

Conclusion

In his detailed analysis Montevecchi lists at total of 91 species. The differential from my final provincial total of 76 species has been explained in my analysis. I freely admit that the complicated nature of the subject matter has likely led to errors on my part which I can only apologize in advance.

Despite the meticulous nature of Lysaght’s work, she was also aware that her records were not complete. She wrote the following in her Introduction:

The record has many gaps but I hope that its publication will draw attention to MSS and other material whose importance has hitherto been overlooked, and will thus enable some other worker to make a more complete assessment of Banks’s collections in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Montevecchi, using the records and opinions of premier early Newfoundland ornithologist, Les Tuck, and the latest research up to publication in the 1980s, has augmented our knowledge of the Banks records.

The level of detail provided by these two ornithological researchers is not repeated in this paper. It has been a humbling experience to attempt to bring the Montevecchi and Lysaght research to the present day. I suspect, like Lysaght, in the future the Banks records for Newfoundland Labrador will continue to evolve.

Bibliography

- Carter, Harold B. 1988. Sir Joseph Banks 1743-1820. London: British Museum

- Forster, J. R. 1771. A Catalogue of the Animals of North America, London: White

- Hough, Richard. 1994. Captain James Cook, A Biography. London: W. W. Norton & Company

- Lysaght, Averill M. 1971. Joseph Banks in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1766. Berkeley CA: University of California Press

- McAtee, W.L. 1962-68. “The North American Birds of Thomas Pennant in Arctic Zoology 1785”. Journal for the Society of the History of Natural History 4: 100-124 London:

- Montevecchi, W. A. and L. M. Tuck. 1987 Newfoundland Birds, Exploitation, Study, Conservation. Cambridge MA: Nuttall Ornithological Club

- Pennant, Thomas. 1784, 1785 Arctic Zoology London: Henry Hughs