Search

Regions

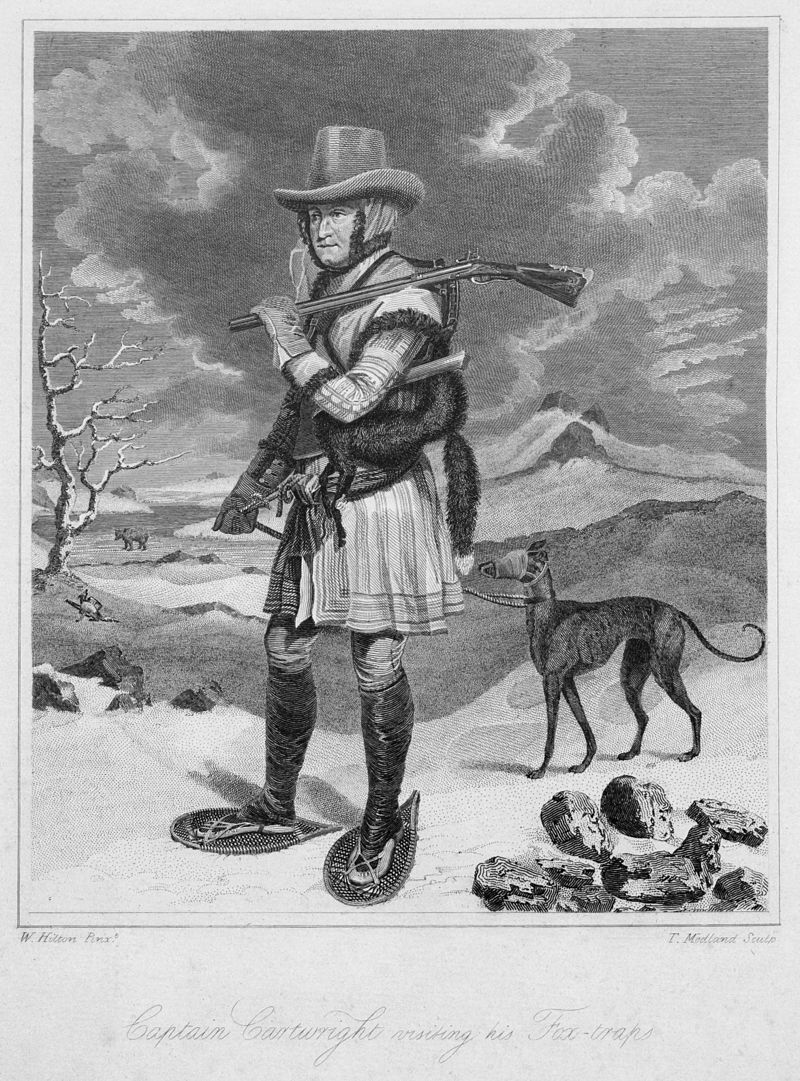

George Cartwright

(1770-1786)

The most important natural history expedition to Canada in the 18th Century was undertaken by Sir Joseph Banks’s trip to Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766. This expedition produced a significant ornithological collection. See the paper on Banks found elsewhere in this section.

This paper discusses George Cartwright (1739-1819),who spent 16 years in southeastern Labrador. Through his published and unpublished writings he made many important contributions to 18th century Canadian ornithology. Cartwright’s records as a resident ranks second, only surpassed in the 18th century by the collections and field notes of Andrew Graham of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the Canadian arctic. Papers on Graham and other naturalists from Hudson’s Bay will be found under 18th century Ontario and Manitoba.

Early Life of George Cartwright

George Cartwright was born at Marnham, Nottinghamshire in 1739. His family came from prominent landed gentry. By the time of his birth the family’s fortunes had suffered decline. Despite the circumstances George and two his brothers, John and Edmund, achieved a measure of fame in Britain in different fields of endeavour.

George chose a career in the military. He entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1753 two years before another British naturalist, Thomas Davies, who also was to make important contributions to Canadian ornithology. For details see papers on Davies under 18th century Nova Scotia and Quebec. In 1754, after one year’s training, and now a Cadet, Cartwright was posted to India. In 1755 he joined the 39th Regiment of Foot with the rank of Ensign. In 1757, after three years service in India, the Regiment was recalled and posted to Ireland. In 1758 Cartwright was promoted to Lieutenant.

In 1760 Cartwright was appointed Aide-de-Camp to the Marquess of Granby. He served in Germany as a Staff Officer with a British Army contingent under the command of Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick. In 1762 he was promoted to Captain but left the service, in debt and on half-pay. Cartwright moved to Scotland where over the next few years he appears to have led a quiet life as a gentleman with a strong interest in hunting.

Cartwright in Labrador

In 1759 British forces captured Quebec. With the fall of Montreal in 1760 French rule in New France came to an end. In 1763, with the conclusion of the Seven Year’s War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Britain assumed control of French territories in Canada including operations in western Newfoundland and southern Labrador. This led to British interest in examining the natural resources in the newly acquired lands.

In 1766 George’s brother, John, was appointed first Lieutenant on the Guernsey, flagship of Sir Hugh Palliser, recently appointed Governor of Newfoundland. In that year George sailed with his brother for the first time to Newfoundland and Labrador. During this sojourn he met Joseph Banks at Chateau Bay in southeast Labrador where the Royal Navy had recently built York Fort, a small blockhouse which housed a small year-around garrison.

Cartwright was attracted to the frontier lifestyle of remote Labrador. After a second visit in 1768 he returned to Labrador in 1770 where he established himself as a trader and businessman operating between the Strait of Belle and Hamilton Inlet. His commercial activities included fishing for salmon in spring, splitting, drying and salting cod in summer, fur trapping in winter and establishing trade with the indigenous peoples.

Over the next 16 years Cartwright pursued his business interests which included taking some Inuit to England in 1772. This visit caused a minor sensation in London society. Cartwright also re-established contact with Sir Joseph Banks. During his visit he was introduced to Thomas Pennant, one of the most important British naturalists of the period. Banks and Pennant encouraged Cartwright’s interest in Labrador flora and fauna. At the time this remote part of eastern Canada was largely unknown to science. Returning to Labrador in 1773, Cartwright commenced sending natural history specimens to Banks. In addition to including a pair of Labrador Ducks, he provided some notes on the seasonal molt of Willow Ptarmigan. Subsequent writings show his interest in natural history was based on a curiosity to observe and record wildlife kindled by his passion for hunting.

Cartwright returned to England in 1786 where he completed a large three-volume work entitled A Journal of Transactions and Events, during a Residence of Nearly Seven Years on the Coast of Labrador Containing Many Interesting Particulars, Both of the Country and Its Inhabitants published in 1792.

Historian G. M. Story, who wrote Cartwright’s biography for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography noted that in addition to his business interests, Cartwright’s Journal contained:

...a detailed seasonal record of the exploitation of coastal resources by one who combined keen entrepreneurial interests with an inextinguishable zest for the chase which made him nature’s nemesis; a finely observed record of natural history and meteorology, and, above all, testimony to a persistent, curious and resourceful mind.

This examination of Cartwright’s Journal has been taken from Charles Wendell Townsend’s edited version entitled Captain Cartwright and his Labrador Journal published in 1911. My use of the Townsend edition is largely the result of its accessibility through the Biodiversity Heritage Library. (BHL).

Townsend noted that Cartwright, living close to the land gained an intimacy with the physical landscape, the climate, the vegetation, and the mammals and birds. His many observations on wildlife were set down in his Journal.

W. E. Clyde Todd wrote an exhaustive ornithology of Labrador, Birds of the Labrador Peninsula and Adjacent Areas published in 1963. Todd’s book is one of the best, if not the best regional history of Canadian avifauna. In his Introduction he included a section “Ornithological History of the Labrador Peninsula”. His assessment of Cartwright’s contribution is limited to one sentence:

Cartwright was a trapper and trader, not an ornithologist, but scattered through the pages of his writings are references to various birds under their vulgar names, some of which are yet in use on this coast.

Cartwright was not included in the almost equally exhaustive Keir Sterling et al edited Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists published in 1997. The many Canadian omissions in this important North American work is a reflection of the gaping hole in research into early Canadian ornithological history. Fortunately many of Cartwright’s original and important unpublished works have been discovered and published since which have greatly enhanced his reputation.

A much more thorough ornithological treatment of Cartwright is provided in Bill Montevecchi’s excellent regional history Newfoundland Birds: Exploitation, Study, Conservation published by the Nuttall Ornithological Club in 1987.

Newfoundland Birds, an introduction to the ornithological history of the birds of Newfoundland and Labrador, was conceived as the first of three volumes. These volumes were intended to update the research and field work of American ornithologists, Harold Peters and Thomas Burleigh who published Birds of Newfoundland in 1951.

The second and third volumes were never published. They were to be based on Montevecchi’s contemporary field study and the records of Newfoundland ornithologist Leslie Tuck. Tuck (1911-1979) was a protege of the famed American ornithologist, Ludlow Griscom. He was appointed Newfoundland’s first Dominion Wildlife Officer in 1949. Until his retirement in 1976 Tuck’s new position enabled him to carry out an extensive study on the province’s bird life. He also secured a role with the Canadian Wildlife Service as a research scientist.

The Peters and Burleigh edition contained an “Annotated List of the Birds of Newfoundland” an historic first attempt at describing all the birds known to have been recorded in Newfoundland. It did not include Labrador. It is unfortunate for Newfoundland and Labrador ornithology that the draft additional Montevecchi volumes, anticipated to be completed by St. John’s ornithologist, Paul Linegar, have never been published.

The New Labrador Papers of Captain George Cartwright (2008) and George Cartwright’s The Labrador Companion (2016)

Fortunately for George Cartwright’s place in Canadian ornithology, his Journal was not his only writing on the natural history of Labrador. In 1979, ethnographer, Ingeborg Marshall discovered a reference to an unpublished Cartwright manuscript long held by Cartwright’s descendants. The discovery and publishing of what turned out to be two manuscripts greatly increases our knowledge of Cartwright and his contributions to Canadian ornithology.

The first manuscript discovered was titled Additions to the Labrador Companion which was written about 1811. The title led to speculation that there was a second manuscript The Labrador Companion which Cartwright had completed in 1810. These documents were held by family members living in South Africa and England. The content of Additions was combined with other Cartwright papers by Parks Canada archaeologist Marianne Stoop and published as The New Labrador Papers of Captain George Cartwright published in 2008.

In 2013 The Labrador Companion was finally discovered. This lead to Stoop’s second volume George Cartwright’s The Labrador Companion, a combined work, which was published in 2016.

Cartwright’s additional manuscripts were intended to provide more complete details on the many aspects of living and working in Labrador, and to correct zoological errors he found in Thomas Pennant’s Arctic Zoology.

It is important to note that Pennant had a habit of not citing his references. No mention of Cartwright is found in either edition (1785, 1792) of Pennant’s Arctic Zoology, Volume II, Class II. Birds.

Stopp extracted Cartwright’s marginal notes from his personal copy of Arctic Zoology which appear in the Appendix of The Labrador Companion. Averil Lysaght in Appendix I of her Joseph Banks in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1766 also discusses Cartwright’s marginal notes. A few excerpts from Cartwright’s copy of Arctic Zoology offers additional insight into his knowledge of Labrador avifauna.

Stopp comments (Companion: 336) that Cartwright noted many errors in Pennant’s writing of species distribution:

Throughout, Cartwright corrects Pennant when the latter failed to note that a bird’s distribution included Labrador and/or Newfoundland. I have not transcribed these many notes.

Canada’s most eminent ornithological historian, Stuart Houston, who reviewed Stoop’s earlier book, The New Labrador Papers (Canadian Field-Naturalist 129; 411) suggests when introducing the subject of Cartwright’s intimate knowledge of the Eskimo Curlew that Stoop did not pay much attention to avifauna, in particular, the curlew.

Since the word “curlew” appears only once in the additions to Cartwright. Stopp might be excused for what was my second disappointment: not mentioning Cartwright’s main claim to fame, the high esteem in which he is regarded by modern ornithologists. I believe most of Stopp’s readers would have appreciated the addition of a few facts from Montevecchi and Tuck’s definitive *Newfoundland Birds* (1987), which rated George Cartwright as “a curious naturalist, a natural historian par excellence”, and the first person to warm of the impending extinction of the Great Auk, the breeding in numbers on Funk Island.

Given Houston’s comments on his review of Papers, I have not examined its contents. I have chosen instead to concentrate on Companion.

Later in his review Houston notes in Gollop, Barry and Iverson’s book, The Eskimo Curlew, a Vanishing Species (1986) mentions that George Cartwright’s 500 specimens, collected mainly for food, provide “the best calendar of comings and goings ever compiled”. They also devote nine pages listing 102 sightings during migration.

George Cartwright the Ornithologist

This paper is an extended biography of George Cartwright and his ornithology including records from Companion. His setting down of his field observations over an extended period of 16 years gives him a unique status in 18th century Canadian ornithology. The only other comparable naturalist is Andrew Graham, the Hudson Bay Company employee who set down his many field observations of birds from that area.

Cartwright met Joseph Banks in St. John’s during Banks’ natural history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766. (Montevecchi). It seems likely that Banks may have impressed on Cartwright the importance of making natural history observations during his residence. Banks is known to have purchased a copy of Cartwright’s Journal.

Cartwright’s centre of operations was on the southeast coast between Cape Charles and Hamilton Inlet. Bird records of the 1766 Banks Expedition are mostly attributed to Chateau Bay, 32 kms south of Cape Charles. Lysaght lists 45 species and Montevecchi 38 species. The disparity is discussed in detail in the Banks paper.

My examination of George Cartwright’s writings lists 44 species. A discussion of the rationale for inclusion or omission of his birds records will be found in the accompanying paper “Cartwright’s Labrador Bird List”. This list includes 13 first records for Labrador, identified with an asterisk. Both Stoop and Lysaght suggest that Cartwright’s bird collection and his field observations sent to Banks were utilized by Pennant. (Companion xxxiii).

A close examination of Cartwright’s many bird observations reveals the true nature of his contribution: a treasure-trove of ecological information about the birds he encountered covering most aspects of the science of ornithology. Readers will note a preponderance of interest in game birds.

Some selected excerpts from his writings below provide useful insight into his ornithological expertise, his surprising level of his curiosity, and his observation skills:

Seasonal Migration and Food Sources of Resident Willow Ptarmigan: Companion 164

They quit the interior parts of the Country about the end of March and return to the Barrens to breed; they remain upon them until Christmas and then retire to such parts of the interior as abound in Birch and Alder, the buds of them, being the food which they live upon during the Winter-season…..the young birds are full grown in less than a month [after the middle of August]. Towards the end of October several broods will pack together, but do not associate long.

Seasonal Changes in Plumage of the Willow Ptarmigan: Journal 141-142

Tuesday, September 28, 1773. This morning I took a walk upon the hills to the westward, and killed seven brace of grouse.- These birds are exactly the same with those of the same name in Europe, save only in the colour of their feathers, which are speckled with white in summer and perfectly white in winter, [Page 142] (fourteen black ones in the tail excepted) which always remain the same. When I was in England, Mr. Banks, Doctor Solander, and several other naturalists having inquired of me, respecting the manner of these birds changing colour, I took particular notice of those I killed, and can aver, for a fact, that they get at this time of the year a very large addition of feathers, all of which are white; and that the coloured feathers at the same time change to white. In spring, most of the white feathers drop off, and are succeeded by coloured ones: or, I rather believe, all the white ones drop off, and that they get an entirely new set. At the two seasons they change very differently; in the spring, beginning at the neck, and spreading from thence; now, they begin on the belly, and end at the neck. There are also ptarmigans [Rock Ptarmigan] in this country, which are in all respects, the same as those I have killed on some high mountains in Scotland.

Cartwright’s observations on the seasonal change in plumage are some of the first in the ornithological literature. This passage also reveals a breadth of interest in the avifauna which pre-dates his residence in Labrador.

Seasonal Movements of Migrant Eskimo Curlews:

The following passage on the arrival and feeding behavior of the now extinct Eskimo Curlew has been taken from Montevecchi’s Newfoundland Birds: 55, which he transcribed from Lysaght:

The birds always make their first appearance on the coast of Labrador between the 28th of July and the 8th of August, and are to be met with in the greatest abundance everywhere along the coast where the ground is clear of timber and provides plenty of heath-berries [on August 26,1770, Cartwright notes curlews feeding on ripe Crowberries and Blueberries - *Journal*:34]. At their first coming they are lean, but soon grow very fat. In general they are plentiful till the middle of September, and some few are to be met with as late as the middle of October, but hard gales or wind from the northwest to the northeast cause them to migrate soon. They are never seen on their return to the northward. Some few are double the size of the rest and not so delicious. I have have known a man to shoot 150 in a day.

Rare Description of a Call of the Eskimo Curlew: Companion 162

Cartwright compares the size of the Eskimo Curlew, which may well be extinct, to the Black-bellied Plover and, most interestingly, a hint of its call note:

They are the size of the Grey-plover; their note very similar...

Observation on the nest and call note of the American Robin: Journal 269

Tuesday, June 29, 1779. I shot a loon, took a (auk's nest, by the pond near the flagstaff) and found a robin's nest. These birds are somewhat bigger than a thrush, are like that bird in shape, but of a more beautiful plumage. They build the same sort of nest, but their note is like the blackbirds; their eggs also, of which they seldom lay more than three, are very like those of the blackbird's.

Observation the nesting details of American Black Ducks: Companion 159

As these birds make their nests in bushes and I never found one of them, do not know number of eggs they lay, but have reason to believe, that they lay nine or ten. Several attempts have been made to rear the young ones, but I never heard of any person succeeding. They are the size of the European Wild-duck.

Calculating Common Eider’s Flight Speed: Journal 77

Friday, May 10, 1771. Early in the morning, leaving Charles to follow with the sealers, and taking Bettres with me, I went to the Table Land in a boat belonging to the garrison, and sent it back immediately on my arrival. In my way hither I measured the flight of the eider ducks by the following method: viz. on arriving off Duck Island, six miles distant from Henley Tickle, I caused the people to lie on their oars; and when I saw the flash of the guns, which were fired at a flock of ducks as they passed through, I observed by my watch how long they were in flying abreast [Page 78] of us. The result of above a dozen observations, ascertained the rate to be ninety miles an hour

Calculation of long-distance flight and digestive rates in Canada Geese: Companion 153

I know that they will eat barley and wheat... a servant of mine once shot one at Chateau, which had Wheat in it, and which it must have picked up in Canada being a great distance from thence, and the bird could not have rested upon its passage, or the Wheat would have been digested.

Taking weights and measurements: Companion 335

Stopp notes that Cartwright makes reference to weights of birds:

On a following blank page, [between pages 6 and 7] in G.C.’s handwriting, is a list of the weights of birds, chiefly raptors but also plover, snipe, wood pigeon [passenger pigeon] etc. These are meant as additional information to Pennant’s field notes.

These figures were not included in Companion. She notes a few measurements elsewhere which are included below:

- Canada Goose: weight between 12 and 15 lbs. (Companion: 150)

- Common Eider: lays 6 eggs each weighing 4 oz (Companion: 160)

- Willow Ptarmigan: lays 6 eggs; weight 16 oz -NF); to 26 oz -Lab. (Companion: 336)

Migration and molt of Canada Geese: Companion 150

They return to Labrador in May; begin to lay their eggs in the first week in June; hatch in early July; can fly in September, and migrate southward in November and December, according to the mildness or severity of the season. When the young ones begin to put out their feathers, the old ones molt all theirs so quick, that they cannot fly sooner than the young ones.

Feeding habits of Canada Geese: Companion 150

...if you walk along the shore, you will discover them by their dung. At low-water, they resort to such Coves and Shores as are shallow and have a particular kind of grass growing upon the bottom, and on which they feed. When the flood has made so high that they can no longer reach that grass at a distance from shore, they gradually draw in nearer and will land at, or a little before high water, and rest themselves for a considerable time... Geese are very fond of a berry which grows upon a moist, Peat soil and is called Baked apple...

Feeding habits and molt of American Black Ducks: Companion 158

When they feed on rotten Kelp, it is always between half ebb, and half flood... From flood to half ebb is the time to find them in the Ponds. As these birds molt all their wing feathers within a few days of each other, they cannot fly until the new ones are sufficiently grown and are easily caught in Nets...

Natural curiosity of American Black Ducks: Companion 159

Undiscovered [by the ducks]... take off your hat and flirt it up and down once very quick; repeat that occasionally, with an interval of half a minute between each time, and curiosity will induce them to swim in close to shore, I never knew that method fail in the Fall, but it will not do in the Spring.

Awareness of the need for conservation: Companion 160

It is bad policy to shoot them upon, or near the islands which they bred upon, nor should you land upon them oftener than once a Week; nor, in truth, ought you to shoot them at all, after they begin to lay.

Conclusion

Cartwright collected bird specimens during his residency in Labrador. With wide knowledge of his Journal published in 1792 he may have been consulted on distribution of species by ornithological writers such as Pennant and Latham. There is no evidence that he supplied any bird specimens new to science.

There is no doubt that with the publishing of the Labrador Companion George Cartwright assumes a unique place in 18th century Canadian ornithology. No other visitor or resident spent so much time in the field thinking about and setting down his experiences with the avifauna of Canada.

Finally Cartwright’s writings offer numerous other interesting observations on avian life in Labrador. A random selection includes the following:

- Setting down arrival dates of some spring and fall migrants

- A vagrant record of a male and female Rose-breasted Grosbeak

- Single Passenger Pigeons collected on August 22, 1775 at Sandwich Bay and at Cartwright Harbour (near the Mealy Mountains) where he noted that both were feeding on Empetrum Nigrum (Crowberry)

- A discussion of the plight of Great Auks on the Funk Islands.

A much more graphic account of the wanton destruction of the Great Auk on Funk Island will be found in the paper on seaman Aaron Thomas who visited there in 1794.

Bibliography

- Gollop, J. B., T. W. Barry and E. H. Iverson 1986. The Eskimo Curlew, a Vanishing Species Special Publication #17. Regina: Saskatchewan Natural History Society.

- Houston, Stuart. 2015. Book Review. “The New Labrador Papers of Captain George Cartwright” The Canadian Field-Naturalist 129:411. Ottawa: Ottawa Field-Naturalists Club

- Montevecchi, William. 1987. Newfoundland Birds: Exploitation, Study, Conservation. Cambridge Mass: Nuttall Ornithological Club

- Pennant, Thomas 1785. Arctic Zoology. Volume II, Class II: Birds. London: Henry Hughs

- Pennant, Thomas 1792. Arctic Zoology. Volume II, Class II: Birds. Second Edition London: R. Faulder

- Sterling, Keir B, Richard P. Hammond, George A. Cevasco, and Lorne F. Hammond Edit, 1997. Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press

- Stopp, Marianne. 2009. The New Labrador Papers of George Cartwright. Montreal and Kingston: University of Toronto Press

- Stopp, Marianne. 2016. George Cartwright’s Labrador Companion. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Qeeens University Press

- Story, G. M. 1983. “Cartwright, George” Dictionary of Canadian Biography 5 Online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cartwrightgeorge5E.html

- Todd, W. E. Clyde. 1963. Birds of the Labrador Peninsula and Adjacent Areas. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Townsend, Charles Wendell. 1911. Captain Cartwright and His Newfoundland Journal. Boston: Dana Estes & Company