Search

Regions

Eleazar Albin

(c1680-1742)

A flood of botanical and zoological specimens, largely from British and French colonies into the cabinets of curiosity of the wealthy in Europe, became a tidal wave by the early years of the 18th century. This huge treasure trove eventually led to the recognition of the need for forming of national and regional museums to arrange and maintain them.

As the 18th century progressed it also encouraged specialization and an increasing degree of professionalism within the study of natural history, widely known at the time as natural philosophy. While botany had always been the prime interest of most natural philosophers through the importance of herbal remedies in medicine, more books were appearing that presaged growing interest in other disciplines.

This division was enhanced by the influential writings of Englishman, John Ray (1627-1705), a man considerably ahead of his time. Ray helped to lay out the groundwork for the division of natural philosophy into separate fields such as botany, ornithology, herpetology and entomology. His many accomplishments include his defining of "species" in his History of Plants (1686) and in The Ornithology of Francis Willughby (1678) outlining a systematic arrangement of birds based on an examination of their external features such as beaks and feet, and internal features such as bone structure and organs. For good measure he posed avian research questions more than four hundred years ago which might offer useful ideas for a PhD. Thesis today.

One of the most important early signs of this specialization was evident in the work of Maria Sibylle Merian (1647-1717) who carried out nature study in the Dutch colony of Surinam between 1699 and 1701. She published her Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium in 1705. Merian's beautiful hand-coloured illustrations paid as much attention to insects as to plants. As noted by Peter Dance in his The Art of Natural History, her work:

was easily the most magnificent work on insects so far produced...[and she showed] a future generation of zoological and botanical artists just what was possible if they combined artistic talent with close of observation of nature. (Dance:50)

After Merian, Europe soon experienced a flood of beautifully hand-coloured illustrated books of a specialized nature. These books show evidence of the flowering of ornithology from its roots in plates displaying stiff and woody colourful male birds in improbable stances and backgrounds to an evolving scientific discipline which records male and females in natural stances in their proper ecological settings. In ornithology, early elements of the advancement of the science are evident in the works of Eleazar Albin, Mark Catesby and George Edwards.

Eleazar Albin was born Eleazar Weiss in Germany about 1680. Perhaps the best portrait of Albin's adult life is drawn by Christine Jackson in her book Bird Etchings: the Illustrators and their books, 1655-1855. She notes that in his youth he appears to have been attracted to zoology and his profession as a painter by his strong interest in insects, flowers and birds because of their beautiful colouring. . His interest may well have been influenced by Merian. Presumably to further his career he emigrated to England, a major colonial power (Germany was not) about 1707, at which time he changed his surname to Albin.

Albin is one a numerous 18th century Germans interested in a career in natural sciences who emigrated in the 18th century. Many had significant contributions to ornithology including Johann Gmelin, Peter Simon Pallas, Georg Steller and Reinhold Forster. Their names will appear in numerous other papers on this website related to early Canadian ornithology of the Hudson Bay naturalists and the Pacific northwest.

Albin established himself as a naturalist and professional water-colour painter. Averil Lysaght the accomplished New Zealand historian of natural history in her Book of Birds notes that by 1720 Albin, who was likely in his early 40s, was an established well-known British naturalist:

In 1719 there was a plan \[by leading British naturalists\] to send a collector to Africa; both Albin and \[Mark\] Catesby were possible candidates.

Lysaght notes that Albin was well known to important patrons such as Sir Hans Sloane, William Sherard and James Petiver. She does not mention if the expedition was ever undertaken. Jackson notes that Catesby was favoured by the patrons but he chose to go America in 1722 and eventually published his pioneering book on American ornithology The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands between 1731-1743. As noted by Dickenson in her book Drawn for Life:

Despite its deficiencies Catesby's work set a new standard in illustrated natural history books published in English and his work remained a reference for American natural history even into the nineteenth century.

Albin struggled financially to produce his first natural history work, A Natural History of English Insects, started in 1714, but not published until 1720.

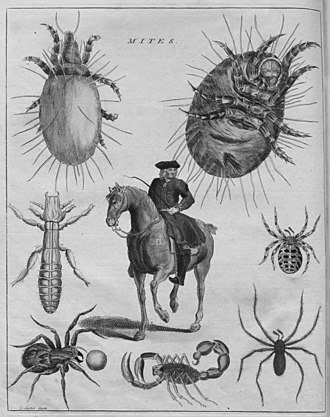

Wikipedia: Frontispiece from 1736 edition of The Natural History of Spiders and other Curious Insects. A rare image shows Albin seated on a horse

Wikipedia: Frontispiece from 1736 edition of The Natural History of Spiders and other Curious Insects. A rare image shows Albin seated on a horse

Over the next thirty years Albin published three other volumes: A Natural History of Birds, A Natural History of Spiders and other Curious Insects and A Natural History of English Songbirds.

Albin was the first European to publish a description and coloured cooper plate etching of a bird species that came from what is now Canada. Self-taught, he used etching (Winearls) instead of engraving which required considerably more skill to handle. According to the Wiki Dictionary of National Biography Albin produced two editions each of three volumes of his A Natural History of Birds as follows:

A Natural History of Birds, with (306) copper-plates curiously engraved from the life and exactly coloured by the author, &c., 3 vols. 4to, London, 1731, 1734, 1738; 2nd edition, 1738– 1740

Volume 3 of the first edition, published in 1738, was entitled A Supplement to the Natural History of Birds. While Volumes 1 and 2 contained British birds, in Volume 3 Albin added bird species from North America, Africa and Asia. As noted by Jackson: "Many of the birds that Albin included are of interest either because they were not previously recognized as native British species or because he provided the first evidence that a foreign species, such as the golden pheasant (Chrys olophus pictus) were present in Britain".

In Supplement Albin etched and coloured an adult Common Loon. On the etching he inscribed the date, August 7, 1735 and described his bird as "The great speckled Loon from Newfoundland".

He provides the following description:

The length from the tip of the Bill to the end of the Tail is thirty-five Inches, to the end of the Claws forty-four; breadth when the Wings are extended four Foot five inches; the Bill was five inches long, black ending in a sharp white Point; the Head and upper part of the Neck are of a dusky brown. It has a white Spot under its Bill, and a Ring of white around its Neck, the lower part of the Neck green: the Back and covert Feathers of the Wing are black spotted with irregular Spots of white; the prime Feathers of the Wings are black, their exterior Edges white; the Breast and Belly are white, the Legs of a brown Colour nine Inches long; the outward Toe which was the longest, was five Inches long. It was Web-footed like a Goose; it feeds altogether on Fish.

Along with his description Albin noted that: "It was brought from Newfoundland, and presented to the Right Honourable the Lord Ilay, who was pleased to lend it to me, to draw its Picture". No doubt Albin obtained many other bird specimens for his bird books from wealthy British collectors such as Lord Ilay.

As noted by Jackson "Albin's birds are recognizable portraits and reasonably true to life, but he knew little of the birds habits, and the information he gave in the short text concerning each species included nothing new...nor was it as good as that contained in Willughby and Ray's Ornithology".

Archibald Campbell (1682-1761), 1st Earl of Ilay, also held the title 3rd Duke of Argyll (1743). According to Wikipedia "He was the dominant political leader in Scotland in his day." Ilay was also a businessman with interests in trade which probably accounts for his acquisition of a bird specimen likely from the Newfoundland fish trade. He was also an enthusiastic gardener who established an estate at Whitton Park Middlesex in 1722. Known by Horace Walpole as the "Treemonger" Ilay imported exotic plants and trees for his estate. No doubt Ilay's many connections offered plenty of opportunity for collecting faunal specimens as well. In addition to these interests Ilay was one of the founders of the Bank of Scotland and a key founder of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. Later in the 18th century the Faculty became the centre for the spread of British interest in natural history, including ornithology, among the professional class of graduating scientists and medical doctors.

Albin's Common Loon was certainly not the first bird specimen collected in Canada. Averil Lysaght in her second more important book, a thoroughly researched minor masterpiece Joseph Banks in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1766 points out that Albin's contemporary, George Edwards (1694-1773), refers to a collection of Newfoundland birds maintained by George Holmes (1662-1749) deputy-keeper of the Queen's menagerie at the Tower of London. She notes that "It was a custom for naval officers to bring specimens back from various parts of the world for the royal collections at the Tower..."

Lysaght remarked that these birds were part of Holmes personal collection "but I have found no details of the collection belonging to George Holmes except the Newfoundland birds described by Edwards". Five of these birds collected from the Newfoundland fishery appear in Edward's initial work The Natural History of Birds published between 1743 and 1751. For details of Edwards' Newfoundland birds, please see the paper on George Edwards under that province.

In reality, given the discovery of the Grand Banks fishery, and Newfoundland's geographic location as the gateway to New France, there are no doubt countless bird observations and specimens date back to the discovery and founding of New France. Cartier recorded Great Auks, Gannets and Common Murres in Newfoundland waters in the Funk Islands during his historic voyages of the 1530s. For details see Jacques Cartier under 16th Century New France.

Scattered through the literature are numerous other records such as those the pioneering North American ornithological historian, W.L. McAtee, who wrote an article entitled "North American Bird Records in the Philosophical Transactions 1665-1800" in the Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History 3:5 (1953). McAtee records a letter dated 1693 written by John Clayton of Wakefield, Yorkshire, which mentions small black divers "off the Banks of New-found Land" McAtee suggests that these birds were Dovekies.

Among the many interesting early records is that of a Great Auk which appears in a painting of birds by the famous French artist, Nicolas Robert (1614-1685) in the King's menagerie at Versailles. Discussion of the painting appears in an article by Arturo Valledor De Lozoya, et al entitled "A great auk for the Sun King" in Archives of Natural History 43 (2016). It is highly likely, as De Lozoya suggests, that this bird came from the Newfoundland fishery, largely dominated in the 17th century by fishermen from Normandy and Brittany.

Early Newfoundland bird records can be examined in considerable detail in Chapter 4, "Early Written Accounts of Birds (1007-1795 A.D)" in Bill Montevecchi's important Newfoundland ornithological history Newfoundland Birds: Exploitation, Study, Conservation published in 1987.

In conclusion, Jackson summarizes Albin's work as follows:

Albin's books added little to the knowledge of birds but were attractive and useful in showing many species in color for the first time. They were small, set a standard of illustration of the bird – and – branch kind introduced the eggs of species for the first time. A few illustrations broke new ground with backgrounds sketched in, and many of Elizabeth's \[his daughter who also sketched and painted\] had more detailed fine grounds and better drawing of birds than those of her father..In doing his own drawing and coloring, perhaps some of his own etching, and by publishing his own first book about birds, Albin set a pattern that was followed by many later bird artists.

There was also French edition of Albin's Natural History entitled Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux. The first French edition of the work was translated by William Derham and published in The Hague by Pierre de Hondt in1750. Other than the translation, no changes appear to have been made to the text or the illustrations. This book contains an image of an immature Common Loon in Volume 1: 72 Plate LXXXII.

The inscription under the image states: "Colyybus Masimus Caldatus The Great Speckled Diver or Loon: 82". The text indicates that this bird was collected on the River Tame in Warwickshire, England.

Bibliography

- Albin, Eleazar. 1731, 1734. A Natural History of Birds Volumes. 1& 2. London: Innys and Manby Printers

- Albin, Eleazar. 1740. A Supplement to the Natural History of Birds. Volume 3. London: Innys and Manby Printers

- Albin, Eleazar and William Derham. 1750. Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux. 3 Vols. Le Hague: Pierre De Honat

- Dance, Peter. 1989. The Art of Natural History. London: Bracken Books

- De Lozoya, Arturo Valledor, David Gonzalez and Jolyon Parish. 2016 "A great auk for the Sun King" in Archives of Natural History Volume 43. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press.

- Dickenson, Victoria. 1998. Drawn from Life: Science and Art in the Portrayal of the New World. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Jaskson, Christine E. 1985. Bird Etchings: the Illustrators and their books, 1655-1855. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

- Lysaght, A. M. 1971. Joseph Banks in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1766. Berkeley and Los Angles: University of California Press

- Lysaght, A. M. 1975. The book of Birds: Five Centuries of Bird Illustration. London: Phaidon Press

- McAtee, W. L. 1957. "North American Birds of Mark Catesby and Eleazar Albin" Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History Volume 3, No 5 Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- Montevecchi, William and Leslie M. Tuck. 1987. Newfoundland Birds: Exploitation, Study, Conservation. Cambridge MA: Nuttall Ornithological Club

- Redford, Ernest. 1885-1900. "Albin, Eleazar". Wiki Dictionary of National Biography. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/DictionaryofNationalBiography,1885-1900

- Wikipedia. Archibald Campbell, the 3rd Duke of Argyll https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ArchibaldCampbell,3rdDukeof_Argyll

- Wikipedia. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Albin, Eleazar https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/DictionaryofNationalBiography,1885-1900/Albin,_Eleazar

- Willughby, Francis and John Ray. 1678. The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, esq. London: John Martyn

- Winearls, Joan. 1999. Art on the Wing: British, American, and Canadian illustrated bird books from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. Toronto: University of Toronto Library