Search

Regions

Aaron Thomas

(1794)

Aaron Thomas Jr. (1762-1799) was born at Wigmore, Herefordshire in 1762. He spent much of his formative years in Ludlow, Shropshire. He was the third child of Aaron Thomas Sr. a prosperous local farmer.

Thomas is best known in Canada for his Newfoundland Journal, an interesting account of life aboard a Royal Navy vessel in the late 18thcentury. Journal also includes observations on the climate, inhabitants, living conditions and wildlife of Newfoundland. An interesting review of Journal by Sarah Glassford, and additional details of Thomas’s life will be found in the bibliography below. This paper discusses his contributions to late 18th century Newfoundland ornithology.

Able Seaman Thomas was one of 220 men who made up the crew of the Boston, a Royal Navy 32 gun frigate. His Journal of his sojourn to Newfoundland covers the period May to November, 1794. Journal was never published during his lifetime. It was eventually acquired by the Murray family of Newfoundland in the late 19th century, edited by a descendant, Jean Murray, and published in 1968. Thomas served on other ships in the Royal Navy. He died of unknown causes while serving on the Lapwing in the West Indies in October, 1799. (Glassford).

Thomas was clearly an educated man and a keen observer who among other interests included random observations of the birds of Newfoundland and Labrador. His late 18th century observations add value to the more well-known nature writings of George Cartwright (1739-1819) who first visited Labrador in 1766. Cartwright lived in Labrador for extended periods until 1786 and published his Diary in 1792.

The two most important observers in 18th Century Newfoundland and Labrador were George Cartwright, who lived in the province for 16 years, and Sir Joseph Banks who visited in 1766. The latter collected an extensive number of bird specimens. For accounts of Cartwright and Bank’s contributions see separate papers on these men.

On his Atlantic crossing Thomas mentions a few birds including on May 2nd “Irish Lords”. Thomas also mentioned very curious birds called “Old Hatts”. These birds are not readily identifiable. Closer to Newfoundland the Boston encountered icebergs on which he noted occasionally carried arctic stragglers he refers to as “Foxes, Sea Lions and Seals” and commented that the Lions “live on the Seals and a bird called Ice Birds.” Thomas remarked on the Lion’s hunting strategy:

The Lion, being the colour of the Ice, he lies down, the Birds light on him in great numbers and become an easy prey. They are about the size of Crows, all white, except their Bills and Feet which are yellow.

It would seem that the Sea Lion was the Polar Bear. The identity of the “Ice Bird” is more problematic. Iceland Gull, a common gull in off shore Newfoundland waters in late May comes closest to fitting the description. The adult appears all white, has a yellow bill and light-coloured pinkish legs.

During his 6 month tour of duty the Boston was based in St. John’s. As part of the Boston’s duties the vessel visited Capelin Bay (Calvert), Ferryland, Aquaforte, the French islands of St. Pierre, Miquelon, Langlade, and settlement at Placentia. Only a few birds are mentioned during these voyages, mostly around the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon including:

Loon species: (between St. Pierre and Langlade)

We presently saw a large Bird not unlike the size of a Goose. I find it is call’d a Loon. Captain Skinner fir’d at it but the Bird dived, and rose again at some distance. We follow’d and fir’d at it several times but unless it is hit on the head it cannot be killed.

Black Guillemot: (while trying to land at Langlade)

On the guns firing a number of Birds flew out of the Cliffs and crevices, quickly took wing and escap’d over our heads. They were the size of a Blackbird, the shape of a Pigeon, and had white under their Wings, their Tails tipt with white, red Feet, and other parts of the Black. They are called Sea Pigeons and are very numerous, frequenting uninhabited rocky and desolate shores.

Bald Eagle (Langlade)

We espy’d an Eagle setting on a dead Stump, on the very summit of an exceeding high Rock. He was fired at but the shot did not tell. The Bird seemed to treat the report, and the noise of the shot against the stones, with perfect contempt, as it did not take to wing for a full half minute after the Gun was fired. It then gave a piercing, sharp, shrill note, left its Perch, took a small circuit, and return’d to the old, dead, white Stump from which it first took its flight. Moving slowly on, within a few yards of the first Eagle, we saw another; nearly the same circumstances attended this as had just passed with that before. We killed neither of them. Their heads were white, their bills yellow, all their bodys of a chocolate colour. There are a number of them on this desert Coast.

Atlantic Puffin (Grand Columbrier, St. Pierre Islands)

The Boston settled in among a major nesting colony consisting of what Thomas suggested was many thousands which he described:

Birds all of one kind and called Puffins or Sea Parrots. Their heads are exactly alike Parrots in point of shape, much about their size, the bodys of them black and white. The head and the beak are the principal beautys of these Birds; the beak is trisecious, and colour’d in shades in perfect unison to the national Cockade of France – blue, white and red. They are amphibious, living on the water by day and on Shore at night. They make holes in the ground like Rabbits, in which they breed. People who go after their Eggs take pick-axes and spades to get at their nests, this is called Puffin digging. But they generally choose such a bold shore for their rendezvous that there is not getting at them.

Thomas encountered Willow Ptarmigan and describes the changing plumage:

In the Northern World where Winter Reigns in all the majesty of unrelenting severity all animals change their Colour. They are generally white in Winter, assuming a dress similar to the then colour of the Earth, which is cover’d with Snow. In Newfoundland in Winter if you kill a Hare it is perfectly white, if you kill a Partridge it is perfectly white, and so the principal part of the Animal creation in this part of the World. In this I perceive the work of something Devine.

Of greatest interest is his writings about the natural history and ornithology of Newfoundland was his setting down his personal experience encountering Great Auks on the Funk Islands (Journal:126-128).

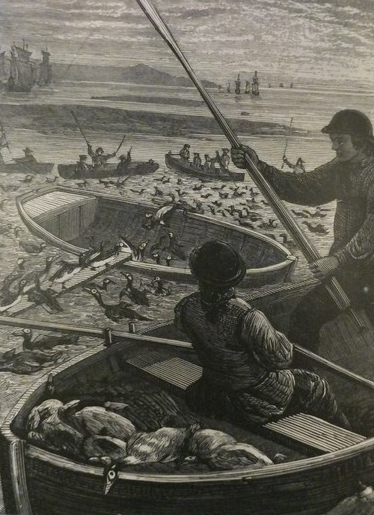

Thomas remarked on the many thousands of Penguins (Great Auks) on Funk Island:

you cannot find a place for your feet and they are so lazy that they will not attempt to move out of your way. If you come for their Feathers you do not give yourself the trouble of killing them, but lay hold of one and pluck off the best of the Feathers. As you turn the poor penguin adrift, with his skin half naked and torn off, to perish at his leisure. This is not a very humane method, but it is the common practice.

Thomas describes first hand how how egg collectors ensured a fresh supply:

You drive, knock and shove the poor Penguins in Heaps! You then scrape all the Eggs in Tumps, in the same manner you would a Heap of Apples in an Orchard in Herefordshore. Numbers of these Eggs, from being dropped sometime, are stale and useless, but you having cleared a space of ground the circumferences of which is equal to the quantity of Eggs you want, you retire for a day or two behind some Rock at the end of which time you will find plenty of Eggs – fresh for certain! - on the place that you had before cleared.

Thomas offers a graphic and gruesome picture of collecting Auks for food:

While you abide on this Island you are in the constant practice of horrid crueltys for you not only skin them Alive, but you burn them Alive also, to cook their Bodys with. You take a Kettle with you into which you put the Penguin or two, you kindle a fire under it, and this fire is absolutely made of the unfortunate Penguins themselves. The Bodys being oily soon produce a Flame; thee is no wood on the island.

He also mentions that the Governor (likely Sir James Wallace) had recognized that the wanton slaughter and passed a law to try to manage it. This may well have been one of the first attempts at environmental legislation in Canada. It did not prevent the ultimate extinction of the Great Auk by the mid 19th Century.

Before leaving Newfoundland Thomas provided the following summary of his knowledge of Newfoundland birds:

Newfoundland has a variety of Water and Land Fowl, many of which are beautifully feather’d, and were a collection in one spot the sight would be new and pleasing to the Eye of the European. Partridge [Willow Ptarmigan] is as large as an English Hen, are white in Winter, except their Red Gills. They are a desirable Bird for eating. Here are Wild Ducks [ducks, eiders and scoter species] and Geese [Canada Goose] of various kinds which frequent the Lakes, Eagles [Bald Eagle] which frequent inaccessible Rocks, Hawks [likely immature Bald Eagles or Osprey] much larger than those in England, Curlews [both Whimbrel and Eskimo Curlew are likely] of delicious taste, Birds of their motions answering the British Blackbird [the Blackbird is a thrush suggesting the common, based on motion, the American Robin], but their colour widely different, Thrushes which are Red [possibly some of Pine Grosbeak, Purple Finch and the Crossbills, all fairly common], Lewes [possibly Northern Gannet which breeds near Lewis in the Hebrides] that are beautifull and large then a Goose, with a vast variety of other Birds of different sizes. The Coast abounds with Sea Birds. Here are Sea Gulls so large that from the extremity of each wing, when extended, measures Four feet [unknown - even the Osprey would be too small], Penguins [Great Auk], Hagdowns [shearwater species], Muirs, Tuirs [Common Murre, possibly both Murre species], Ice Birds [Iceland Gull] Mother Carey’s Chickens [Leach’s Storm-Petrel], Loons [Common Loon], Noddys [likely Razorbill] , Sea Parrots [Atlantic Puffin], Sea Pigeons [Black Guillemot] and a number of other Sea Fowl.

Over the course of his visit Thomas assembled a collection of birds probably with a combination of shooting and purchasing from locals. Unfortunately the content of his collection is merely mentioned in passing:

During my emigration in Newfoundland I collected a small assortment of Birds of the Country. These I got stuffed and had them hung in my Berth. They consisted of Lews [Northern Gannet], Wild Ducks, Sea Parrots [Atlantic Puffins] etc...

Given his summary of Newfoundland birds provided above it seems likely that many of the birds mentioned ended up in his collection. What happened to this collection is unknown.

Other than the accounting of his experiences with Great Auks on the Funk Islands, Aaron Thomas’s ornithological accounts of Newfoundland birds are not particularly important to early Newfoundland and Labrador ornithology, or Canadian ornithology. Their importance lies in the rare 18th century first hand graphic detail of slaughter which forecast the extinction of the Great Auk. Eighteenth century ornithological observations in the province by a published author is surpassed only by the writings of George Cartwright as demonstrated in Marianne Stopp’s the recently published George Cartwright’s The Labrador Companion.

I am indebted to author and poet Denis Robillard of Windsor, Ontario for suggesting that I examine Thomas’s writings.

Bibliography

- Fuller, Errol. 1999. The Great Auk. Great Britain: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Kearley, G. 2008. Links in the Chain. Online Publisher: Read Books

- McAtee, W. C. 1957. Folk Names of Canadian Birds. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada

- Thomas, Aaron. 1968. Edit Jean Murray. The Newfoundland Journal of Aaron Thomas. Toronto: Longmans Canada Limited

- Glassford, Sarah. Online Seaman, Sightseer, Storyteller, and Sage: Aaron Thomas's 1794 History of Newfoundland URL: https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/nflds/article/view/5888/6899