Search

Regions

The Third Cook Expedition

(1778)

Introduction

As early as the 16th century European explorers sailed up the west coast of North America looking for the terminus of the Northwest Passage. This mythical route was presumed to connect the Atlantic to the Pacific and thus provide a much shorter route for European trade with China and the Far East.

A serious attempt to find it was undertaken by Captain James Cook on his ill-fated third voyage with Resolution and Discovery between 1776 and 1780. Avid Mackay in his In the Wake of Cook, Exploration, Science & Empire, 1780-1801 noted that Cook's first two major south seas expeditions included important scientific developments:

- the selection of scientists to accompany official expeditions;

- the collection of important botanical and zoological specimens;

- the use of the latest scientific instruments;

- more rigorous journal-keeping.

Some of these advancements can be attributed to Sir Joseph Banks. Banks had organized and led a collecting trip to Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766. He also collected botanical and zoological specimens as a member of Cook's first expedition to the south seas in 1768-1771. In 1772 Banks became the unofficial director of Kew Gardens which soon became the focal point for British botanical activity. He used his influence tirelessly to promote the interests of science and scientists, including outfitting later Cook expeditions.

One might expect that Cook's exploration in the Pacific Northwest of North America would result in a significant advancement of our knowledge of the ornithology and natural history of British Columbia. While the results were significant, they were greatly hindered by numerous factors discussed below.

The scientific results of the first and second Cook expeditions showed a level of co-operation between the Royal Navy and the scientific community. It was not repeated with the third. Cook harboured resentment of Banks's perceived interference during the first expedition. Cook's distaste for scientists grew over disagreements with Reinhold Forster and his son, Georg, who were the official Royal Society scientists appointed to accompany his second voyage. As pointed out by Layland In Nature's Realm Early Naturalists Explore Vancouver Island quoting Cook in John Beaglehole's The Life of Captain James Cook.: 502 "Curse all scientists and all science into the bargain!"

Unfortunately for Canadian ornithology, the British government did not want to repeat the conflicts on Cook's third voyage. As a result the Admiralty deliberately chose not to send a trained specialist dedicated only to natural history. This policy was repeated with the 19th century Ross and Parry expeditions to the Canadian arctic and the Franklin expeditions. They succeeded through outstanding individual efforts. No such effort materialized in he third Cook expedition.

The British government's downplaying of the importance of the natural sciences and ornithology in its expeditions to Canada may have also been affected by at least two other factors. The British founded colonies in Newfoundland as early as 1610. Over more than one hundred and fifty years they had considerable insight into the natural history of Hudson's Bay Company lands in the Canadian arctic and prairies. In 1760, with the fall of Montreal, Britain assumed control of all of eastern Canada from France. By the late 18th century Britain had limited interest in the further exploration of the known limited economic benefits of Canadian botanical and zoological resources. This disinterest likely paled with the potential economic benefits, in particular tropical plants, in its new possessions such as India and Australia.

Despite these numerous negative influences, the ornithological results of the Cook expedition were still the most significant of the many expeditions to the Pacific Northwest in the late 18th century.

In the 1770s, the Russians, known to be in Alaska, were rumoured to be establishing fur-trading posts down the west coast. As part of Cook's third voyage he was instructed to report on Russian activity in the area as well as look for the western entrance to the Northwest Passage in the Bering Sea. As noted by Michael Layland in his pioneering book on west coast natural history In Nature's Realm; Early Naturalists Explore Vancouver Island, Cook was also instructed to:

You are to carefully observe the nature of the Soil & the produce thereof; the Animals & Fowls that inhabit or frequent it.......and in case there are any, peculiar to such places, to describe them as minutely, and to make as accurate drawings of them, you can..... (*Realm*: 29)

Travelling with Cook in Resolution was the ship's doctor, William Anderson, an experienced naturalist, who would be in charge of fulfilling this function. Anderson also accompanied Cook on his second voyage. Anderson's collection activities were to be assisted by the artist, William Ellis, listed as the Surgeon's mate. Also accompanying Cook was the expedition's official artist, John Webber. In terms of the ornithological artwork which has survived, limited research suggests that Ellis's contributions were more significant.

Charles Clerke was Captain of the expedition's second ship, Discovery. Clerke was a veteran of Cook voyages having participated in his two previous expeditions. He kept a Journal which recorded natural history observations. Layland notes that Clerke had developed knowledge and interest in natural history through his interactions with the naturalists of the first two expeditions. Some of the contents of Clerke's Journal were examined and published by Beaglehole in his 1968 Cook biography mentioned above. Excerpts in Layland's book suggest that Clerke's knowledge of birds was limited and his contributions were not significant.

With the death of Cook, James King, second lieutenant on the Discovery, was given the task of editing the official version of Third Voyage entitled A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean Undertaken by the Command of His Majesty, published in 1784. King was also a veteran of Cook's first two voyages. The details of birds provided in King's account of the expedition in British Columbian waters are set out in the ornithological results detailed below. As noted by Layland, bird records from the voyage were mostly devoid of solid information on where species were collected and who collected them. In the official version King did not avail himself of the contents of Clerke's Journal.

As in his previous voyage with Cook, Anderson kept a Journal in which he entered notes on the flora and fauna he collected. In 1777, a year before Resolution reached British Columbia, Anderson contracted consumption. He stopped writing his Journal on June 3rd, 1777 when the Resolution was exploring Cook's Inlet. Anderson died on August 1, 1778 while the Cook was exploring the Bering Sea. The expedition also lost the services of Clerke who also died of consumption at Kamchatka in 1778.

Given the difficulties encountered in assessing the ornithological records of the Third Cook expedition at the time, more recent research has been undertaken to compile and reconcile the various written accounts and attempt a species list. A major effort was undertaken by Theed Pease (1871-1971) in his book Birds of the Early Explorers in the Northern Pacific published in 1968. Pease examined the Cook records, all the other expeditions of the Pacific Northwest including those to Alaska, and the research by Erwin Stresemann who wrote about the results of the third Cook expeditions published in 1950 in Ibis, discussed below.

Beaglehole's book on Cook was published in 1968. In addition to including material from Clerke's Journal for the first time, Beaglehole consulted widely with ornithologists in Vancouver and London. As a result his work provides an assessment of all the Northwest Pacific expedition bird records.

Key places where the expedition members collected in 1778 included twenty-eight days at Nootka, a week in mid-May at Prince William Sound, and 5 days in late June-early July on Unalaska Island, Alaska. After searching for the Northwest Passage in the Bering Strait, they returned to the Bering Sea spending 5 days in Norton Sound in mid-September and an additional 3 weeks at Unalaska in October before the fatal voyage to Hawaii.

After Cook's death the Resolution sailed for Petropawlowsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian far east in late April, 1779, leaving in early June for the Bering Straits and returning to Kamchatka in August. The expedition left in October for Manila. It arrived back in England in August, 1780.

Ornithological Results of the Cook Expedition in British Columbia

The Cook expedition reached Nootka, British Columbia, on March 29, 1778 and remained until April 26th. King's official account noted the following land birds:

Those (birds) that frequent the woods are crows [Northwestern Crow] and ravens [Common Raven), not at all different from the English ones; a bluish jay [Steller's Jay] or magpie, common wrens [Pacific Wren], which are the only singing bird we heard; the Canadian or migrating thrush [American Robin], and a considerable number of brown eagles with white heads and tails [Bald Eagle]; which, though they seem principally to frequent the coast, come into the Sound in bad weather and perch in the trees. Among some other birds that the natives either brought fragments or dried skins, we could distinguish a small species of hawk [unidentifiable], a heron [likely Great Blue Heron], and the alcyon, or large crested American kingfisher [Belted Kingfisher].

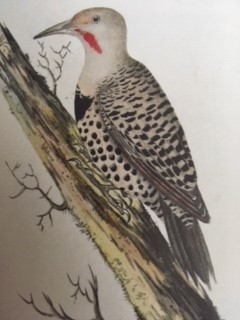

King also describes other birds from Nootka with enough field marks to identify them, including Red-breasted Sapsucker and Red-shafted Flicker (Northern Flicker), Dark-eyed Junco and Surfbird. He also mentions a hummingbird which Ellis drew, the Rufus Hummingbird.

King noted the following birds along the Pacific coast likely from British Columbian and Alaskan waters:

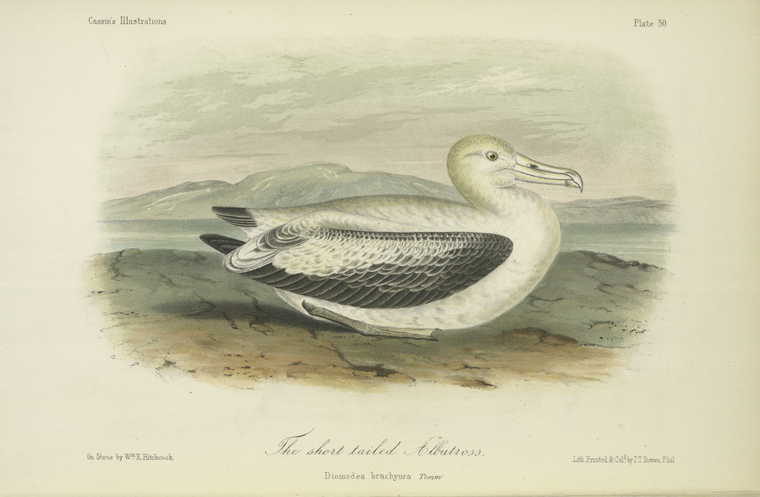

The Quebrantahuessos gulls [Short-tailed Albatross] and shags [Cormorant species] were seen off the coast.........we saw two sorts of wild ducks; one black with a white head [Surf Scoter] which were in considerable flocks, the other white with a red bill [Common Merganser], but of a larger size, and the great lumme or diver [Common Loon], found in our northern countries. There were also seen, once or twice, some swans [swan species]...... on the shore..........we found another, about the size of a lark, which bears the affinity to the burre [shorebird species], and a plover [plover species] differing very little from our common sea-lark.

In another passage King provides enough detail on the shags (European term for cormorant) mentioned above to identify them as Pelagic Cormorants.

The identity of "Quebrantahuessos gulls" as Short-tailed Albatrosses is an interesting bit of Canadian ornithological history worth repeating. Theed Pearse understood that King's use of the word "quebrantahuessos" was a term mariners applied to Giant Petrel, a very large mostly brown seabird of the southern oceans. Since this genus is not found in Northwest Pacific waters he suspected the word was applied to the somewhat similar-looking immature Short-tailed Albatross which can take twelve years or more to reach full adult plumage. Additional information on Pease and the Short-tailed Albatross will be found in the paper on James Colnett.

Biologist Nancy McAllister who examined bird bones in a midden excavated at Nootka, identified the bones of the Short-tailed Albatross. Indeed Layland notes that she found albatross bones so prevalent in the midden that it "could be referred to as an albatross midden". Originally foraging in summer to the Pacific Northwest, now rare, Layland suggests "Their extirpation...[is related to]....depredation of plumage traders in the 19th and early 20th centuries at the birds' nesting grounds on island near Japan".

It is interesting to note that in Charles Fothergill's writings in southern Ontario (1817-1840), one of the very few non-Ontario birds mentioned was the Short-tailed Albatross. In the McGillivray MSS: 285-286 he provides a description of this species in the following entry:

Albatross: A species is found on the coast of the Pacific, west of the Rocky Mountains that has the body and head white (286) the tail and wings grey. The bill very similar to that of a large gull and 7 inches in length, of a pale pink colour. The legs a very pale blue. The wings are very narrow and pointed and measure from tip to tip 7 feet 10 inches sometimes upwards of 8 feet. The natives sometimes kill them and bring them in to trade with the fur merchants.

Fothergill does not provide a reference for his undated entry. The details provided suggest that it likely came from pioneer British Columbia fur trader and explorer, Simon Fraser, who set up trading posts in British Columbia between 1805-1808. Fraser took up residence in eastern Ontario about 1818. Fothergill and Fraser shared a common interest in natural history. He cited Fraser's western Canadian mammal observations in his Quadrupeds manuscript dated 1830. For details see the Charles Fothergill papers under 19th century Ontario.

Michael Layland examined the drawings of Surgeon's Mate/Artist, William Ellis, in the Natural History Museum. Layland provides illustrations of four birds in his book collected and painted by Ellis in the Pacific northwest. While some were recorded at Nootka, the paucity of the record keeping cannot tie any of the images specifically to Nootka specimens. All are held by the Trustees of the Natural History Museum in London:

| Page | Species | British Museum Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 27. | Rufus Hummingbird (male) | Plate #32 |

| 28. | Tufted Puffin | Plate #37 |

| 37. | Red-shafted Flicker | Plate #19 |

| 38. | Varied Thrush/ Amer. Robin | Plate #74 |

| 126. | Pigeon Guillemot | Plate #49 |

The Captain of Discovery, Charles Clerke's contribution to our knowledge of Canadian ornithology appears fairly limited. Of most interest is the following passage in his Journal from Nootka as quoted by Layland from Beaglehole:

2 or 3 species of Ducks, among which was the Mallard, the red-breasted Goosander [Red-breasted Merganser] and s small species of Goose, of a dark, dirty brown colour [Brant].

After the return of the expedition the botanical and zoological specimens were divided primarily between Sir Joseph Banks and the museum of Sir Ashton Lever. Banks also acquired 96 drawings of birds completed by Ellis over more than four years of the expedition. With few exceptions only one bird of each species was collected.

Fortunately, both John Latham and Thomas Pennant were collecting material for their new volumes. Lathams' General Synopsis of Birds (1781-1785) and Pennant's Arctic Zoology. (1784-1792). Since neither British author followed the Linnean method, the claim for the first description of Cook's birds fell to Johann Friederich Gmelin who copied their descriptions and published them in the 12th Edition of Linnaeus' Systema Naturae. (1789). The Gmelin family is discussed in the paper on Pallas. Gmelin also played an important role in publishing details of specimens new to science from the Hudson's Bay Naturalists. Discussion on these important collectors will be found in papers under 18th century Ontario and Manitoba.

Banks's specimens and artwork from the Cook expedition were given to the British Museum. The specimens were largely destroyed by a combination of poor preparation in the field and neglect at the Museum. The Leverian collection was eventually sold and widely dispersed. Two Cook specimens ended up in the Vienna Museum. Layland noted that Theed Pearse, who compared the artwork of Ellis and Webber, commented that Webber's were ‘distinctly the better".

The scattered ornithological records of the Cook Expedition were not well known when Canada's most important 19th century ornithologist, John Richardson, naturalist of the Franklin expeditions, published his Fauna Boreali Americana. Volume II: The Birds in 1831. Richardson noted:

Captain Cook's third voyage, in 1778-8, contains some information respecting the animals of the north-west coasts of America and Behring's Straits, but, unfortunately, no figures of the birds were published; and the compendious notices which are contained in the works of Pennant and Latham, defective as they are in details of structure, are, in many instances, insufficient to enable us to identify the species, as to ascertain their proper situation in the system. (Boreali: xi)

Despite these comments Richardson was to publish a table which listed all known Canadian and American bird species which included numerous species whose distribution he described as "across the continent" or "west of the Rocky Mountains". He includes in his table known records from the Cook expedition and other expeditions to the area and early 19th century field research by fur-traders and naturalists such as David Douglas.

In a special paper on early 19th century British Columbia ornithology I examine Richardson's 1831 west coast bird list and compare and contrast it with what we now know from the extensive 18th century written British Columbia historical record.

One of the most comprehensive efforts to describe all of the birds found along the west coast of North America was undertaken by eminent ornithologist Erwin Stresemann. Stresemann was the author of Ornithology From Aristotle to the Present, the pioneering history of the development of the science of ornithology written in 1975. In an earlier work in 1950 he published an article entitled "Birds Collected In the North Pacific Area During Capt. James Cook's Last Voyage (1778 and 1779)". Ibis 91:244-255. Stresemann identified more than 70 species which were collected in the north Pacific and arctic areas.

Efforts to identify birds of the Pacific northwest with scant information is a very difficult exercise. The work of Pearse and Beaglehole has not been examined in detail. For this paper I am relying on the research of Michael Layland and the reputation of Stresemann..

Of great importance in Stresemann's research was his ability to tie specimens to specific locations. Stresemann mentions sixteen species attributed to Nootka, the prime collecting site in British Columbia. In his list (Ibis:249-253) he provides important reference information from the official voyage account, authors Gmelin, Pennant and Latham and others, and specimens found in collections etc. Stresemann identifies fourteen birds. Six of the sixteen birds (two at genus level) new to science are delineated with an asterisk:

- Snow Goose (Chen hyperboreus hyperboreus)

- Rufous Hummingbird* (Selasphorus rufus)

- Bald Eagle (haliaetus leuocephalus)

- Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)

- Dunlin (Calidris alpina sakhalina)

- Least Sandpiper (Limonites mitutilla)

- Wandering Tatler* (Heteroscelus incanus)

- Tringa species (Tringa sp.)

- Red-breasted Sapsucker* (Sphyrapicus various ruber)

- Red-shafted Flicker* (Colaptes cafer)

- Steller's Jay* (Cyanocitta stelleri)

- Kinglet species (Regulus sp)

- Varied Thrush (Turdus nuevius)

- American Robin (Turdus migratorius)

- Dark-eyed Junco ((Junco oreganus oreganus)

- Golden-crowned Sparrow* (Zonotrichia coronata)

To the Stresemann list, additional species discussed in this paper, largely from King and Clerke, can be tied to Nootka or British Columbia. These bird records lack scientific rigour. All occur (except the Albatross) in British Columbia today. It is a fairly safe assumption, based on the accounts that they were known to occur in British Columbia in the late 18th century:

- Brant

- Mallard

- Surf Scoter

- Red-breasted Merganser

- Common Merganser

- Surfbird

- Short-tailed Albatross

- Pelagic Cormorant

- Common Loon

- Belted Kingfisher

- Pacific Wren

- Common Raven

- Northwestern Crow

An examination of the Ellis illustrations at the British Museum of Natural History may reveal a few more species. It is possible that some of these might be tied to British Columbia.

Other Cook expedition records from Alaska in Stresemann's Ibis article, which itemize North American birds new to science, are as follows:

Alaska: Prince William Sound:

- Surfbird (Aphriza virgata)

- Marbled Muleteer (Brachyrhamphus marmoratus)

- Savanna Sparrow (Passerculus sand wichensis)

Alaska: St. Matthew Island:

- Ancient Murrelet (Synthliborhamphus antiquus)

- Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia)

Alaska: Unalaska:

- Least Auklet (Aethia pusilla)

Alaska: North of Bering Strait:

- Red Phalarope (Phalaropus fulicarious)

- Fork-tailed Petrel (Oceanodroma furcata)

- Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla flava)

Alaska: Norton Sound:

- Gray-headed Chickadee (Parus cinctus)

The Cook expedition's report which revealed the wealth of sea-otters along the coast and the potential of selling them for huge profits in China, had the immediate impact of luring American, British, Spanish and French traders into the area. This short boom through the 1780s and 1790s resulted in a flurry of activity which opened up the Pacific Northwest for the first time.

The Cook collection from Nootka provided the best ornithological records from British Columbia in the 18th century. Numerous Spanish, French, British and Russian followed before the end of the century. Each is examined for its contributions to Canadian ornithology in additional papers in this section of the website.

Bibliography

- Beaglehole, J. C. Edit. 1974. The Life of Captain James Cook. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

- Cook, James. 1784, Edit. James King. A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean Undertaken by the Command of His Majesty , 3 Vol. London: G. Nichol and T. Cadell

- Ellis, William. 1792. An Authentic Narrative of a Voyage performed by Captain Cook and Captain Clarke in His Majesty's Ships Resolution and Discovery in the Years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779 and 1780. London: G. Robinson, J. Sewell and J. Debrett

- Latham, John. 1781-1785. A General Synopsis of Birds 3 Vols. London: Benj. White, Leigh & Sotheby

- Layland, Michael. 2019. In Nature's Realm; Early Naturalists Explore Vancouver Island. Vancouver: Torchwood

- Linnaeus, Carl. Edit. Johann Friederich Gmelin, 1789. Systema Naturae. 12th Edition. 3 Vols. Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius

- Mackay, Avid. 1985. In the Wake of Cook, Exploration, Science & Empire, 1780-1801. London: Crom Helm

- Pease. Theed 1968. Birds of the Early Explorers in the Northern Pacific. Comox, B.C. Self Published

- Pennant, Thomas. 1784-1792. Arctic Zoology. 3 Vols. London: R. Faulder

- Stresemann, E. 1949. "Birds Collected In the North Pacific Area During Capt. James Cook's Last Voyage (1778 and 1779)". Ibis 91:244-255

- Stresemann, E. 1975. Ornithology From Aristotle to the Present. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press